Authors: Dean Leffingwell with Juha-Markus Aalto

Agile development practices introduced, adopted and extended the XP-originated "User Story" as the primary currency for expressing application requirements within the agile enterprise. The just-in-time application of the user story simplified software development and eliminated the prior waterfall like practices of overly burdensome and overly constraining requirements specifications for agile teams.

However, as powerful as this innovative concept is, the user story by itself does not provide an adequate, nor sufficiently lean, construct for reasoning about investment, system-level requirements and acceptance testing across the larger software enterprises project team, program and portfolio organizational levels. In this whitepaper, we describe a Lean and Scalable Agile Enterprise Requirements Information Model that scales to the full needs of the largest software enterprise, while still providing a quintessentially lean and agile subset for the agile project teams that do most of the work.

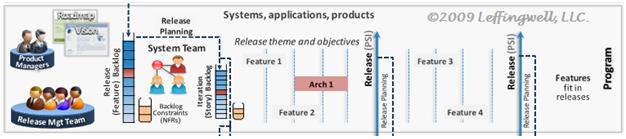

The Big Picture of Enterprise Agility

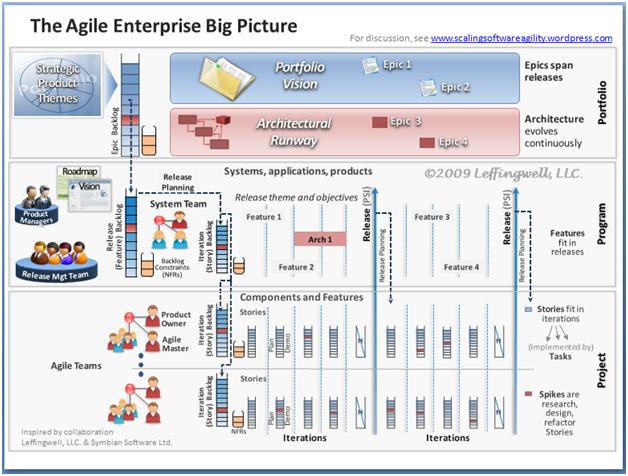

In my Big Picture blog series1, I've attempted to capture the essence of enterprise agility in a single graphic, so as to better communicate the gestalt of "what this will all look like" after an agile implementation. As this serves as the larger organizational, process and requirements artifact context for the requirements information model, Figure 1 below is an illustration of the Big Picture.

Figure 1 - The Big Picture of Enterprise Agility

While the details of this picture are outside the scope of this whitepaper, relevant highlights include:

-

Development of large scale systems is accomplished via multiple teams in a synchronized "Agile Release Train" a standard cadence of time-boxed iterations and releases.

-

Releases are frequent, typically at 60-120 day maximum boundaries.

-

There is a separation of product definition responsibilities at the project, program and portfolio levels.

-

Different requirements artifacts - Stories, Features, and Epics - are used to describe the system at these different levels.

The Requirements Model for Agile Teams

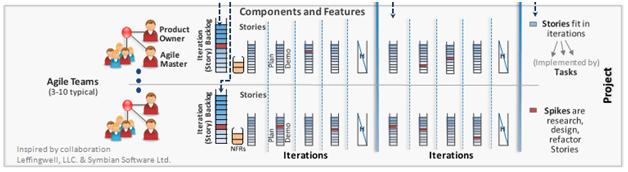

Of course, since the Agile Teams develop and test all the code, they play the most critical role within the agile enterprise. In the Big Picture, they are depicted at the "project level" as indicated below.

Figure 2 - The Agile Team in the Enterprise

Stories and the Iteration Backlog

Since the efficiency of these teams is paramount, we need to assure they apply the simplest and leanest possible requirements model. In agile, that typically takes the form of the simple story, each of which is contained in a prioritized backlog, as figure 3 illustrates.

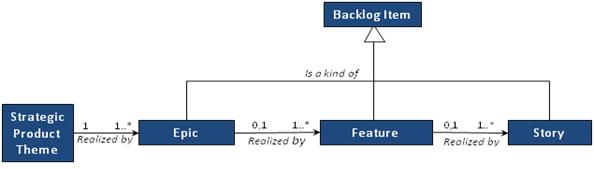

Figure 3 - A Story is a kind of backlog item

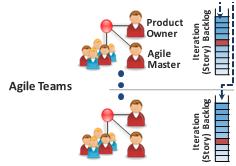

First, we note that Story is a "kind of" Backlog Item. (As we will see, this also implies that there are other kinds of backlog items as well.) In the Big Picture, we described this particular backlog as the Iteration (Story) Backlog as can be seen below.

Figure 4-Stories and the Iteration Backlog

The team's Iteration (Story) Backlog consists of all the work items the team has identified. In the requirement model, we call these work items Stories because that's what most agile teams call them. (Strictly speaking, "work items" is probably a better term, but we aren't trying to fight agile gravity with this meta-model!) So a Story is a work item contained in the team's iteration backlog.

User Stories

While that definition is simple, it belies the underlying strength of agile in that it is the User Story that delivers the value to the user in the agile model. Indeed, the user story is inseparable from agile's goal of insane focus on value delivery, and it is the replacement for what has been traditionally expressed as software requirements. Originally developed within the constructs of Extreme Programming, User Stories are now endemic to agile development in general and are taught in Scrum as well as XP.

A User Story is a brief statement of intent which describes something the system needs to do for the user. As commonly taught, the user story often takes a canonical (standard) form of:

As a <role> I can <activity> so that <business value>

LOTS have been written on applying User Stories in agile development so there is no need to elaborate further here. However, in the model so far, the User Story is not explicitly called out, but rather is implied by the Story class. To make the User Story explicit, we need to extend the simple model a little as seen below:

Figure 5-Stories can be user stories or other work items

With this small addition, we now see that the backlog is composed of User Stories and Other Work Items, which include things like refactors, defects, support, research spikes and infrastructure development.

Stories are Implemented via Tasks

While, on the surface, agile development may appear to be less disciplined than traditional iterative or waterfall development, in reality, nothing could be further from the truth. Agile is the most disciplined software development model in use today. Part of that discipline is assuring that stories can be developed, tested and delivered to the baseline in the course of short iteration. Assuring that requires daily and intense cooperation from teammates. Therefore, each team member estimates the Tasks that are necessary to achieve a story. Since Tasks are explicit in agile, they must be explicit in our model as well:

Figure 6-Stories are implemented via tasks

As implied by the 1-to-many (1..*) relationship expressed in the model, there is often more than one task necessary to deliver even a small story.

Acceptance Tests: All Code is Tested Code

Ron Jeffries, one of the creators of XP, used the neat alliteration, Card, Conversation and Confirmation to describe the three elements of a User Story.

-

Card represents the 2-3 sentences used to describe the intent of the story.

-

Conversation represents fleshing out the details of the intent of the card in a conversation with the customer or product owner.

-

Confirmation represents the Acceptance tests which will confirm the story has been implemented correctly.

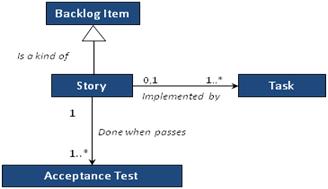

With this simple alliteration and XPs zealousness for "all code is tested code" we have an object lesson in how quality is achieved during, rather than after, actual code development. In our model, however, we treat the Acceptance Test an artifact distinct from the (User) Story itself, and associate each story with one or more acceptance tests as indicated below:

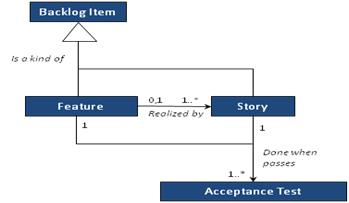

Figure 7- A story is not done until it passes an acceptance test

In so doing, the model is explicit on its insistence on the relationship between the Story and Acceptance Test, thereby assuring quality. This is seen in the 1 to many (1..) relationship (i.e. every story has one or more Acceptance Tests) and in the fact that a Story cannot be considered complete (done when passes) until it has passed the Acceptance Test(s).

Summary of the Model for Agile Teams

Perhaps this didn't seem like an overly complex discussion, and for most agile teams, these few unarguably-agile artifact types are all that is needed for a lightweight agile process. And yet, the apparent simplicity disguises a somewhat more complex background, as the summary model shows:

Figure 8-The full model for agile teams

Why the Team Model is Lean and Scalable

Relative to the "advertising claims" of our lean and scalable model, it's worth noting why the model is lean and scalable:

|

It is Lean

|

It is Scalable

|

|

Simplest possible agile artifact types

|

No limit to the number of teams

|

|

Just-in-time story development eliminates requirements specification and inventory

|

No limit to the number of stories

|

|

All code is tested code - no untested code inventory either

|

If all code is tested code, the system will have inherent quality too

|

|

Simple backlog construct facilitates a pull/kanban system

|

Separation of backlogs simplifies administration and tooling

|

The Model for Agile Programs

For smaller software projects and small numbers of teams, this model is fully adequate to support quality development in an agile manner. Indeed, the model and artifacts so far are so simple and commonly used that one would not consider it to be a "requirements model" at all.

However, at enterprise scale, things are more complex and this simplistic model does not scale well to the enterprise challenge. The reason is fairly simple, as nifty as the story construct is, it is too fine grained a construct for the enterprise to reason with when communicating vision, planning or assessing status. One problem is in the math. Let's assume:

-

A modest sized enterprise (or system or application within a larger enterprise) that requires say, 200 practitioners, or 25 teams to deliver a product to the market.

-

The enterprise delivers software to the market every 90 days in five, two week iterations (plus one hardening iteration).

-

Each team averages 15 stories per iteration

-

Number of stories that must be elaborated and delivered to achieve the release objective= 25*5*15= 1,875!

How is an enterprise supposed to reason about such a process?

-

What is this new product going to actually do for our users?

-

If we know we have 900 stories complete, we may be about 50% done, but what do we actually have working? How would we describe 900 working things?

-

How will we go about planning a release than contains 1,875 things?

A second problem is in the language of the User Story. Even if I know 100 things that "as a <role> I can <activity> so that <business value>", can do, what Features does the system offer to its user and what benefits does it provide?

So for many enterprises, the simpler team model does not scale to the program level set of challenges, and a new model must be applied:

Figure 9-The model for agile programs

In this model, the level of abstraction of defining system behavior is elevated to the system/feature level, and the level of planning and management is elevated to the release.

Feature

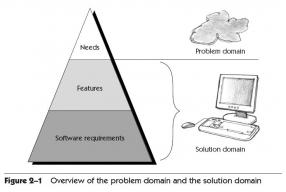

By using the word Feature for this higher level abstraction, we have the security of returning to a more traditional description of system behavior, as Feature is a traditional artifact that has been well described in a number of software requirements texts2. Generally, Features are services provided by the system that fulfill a user need. They live at a level above software requirements and bridge the gap from the problem domain (understanding user needs) to the solution domain (specific requirements intended to address the user needs) as the graphic from that text below shows:

Figure 10-Traditional "requirements pyramid"

We also posited in that text that a system of arbitrary complexity can be described with a list of 25-50 such features. That simple rule of thumb allowed us to keep our high level descriptions exactly that, high level, and simplified our attempts to describe complex systems in a shorter form.

Of course, in so doing we didn't invent either the word "Feature" or the usage of the word. Rather, we simply fell back on industry standard norms to describe products in terms of, for example, a Features and Benefits Matrix as was often used by product marketing to describe the capabilities and benefits provided by a new system. Moreover, by applying this familiar construct in agile, we also bridge the language gap from the agile project team/product owner to the system/program/product manager level and give those who operate outside our agile teams a traditional label (Feature) to use to do their traditional work (i.e. describe the thing they'd like us to build).

Also, the ability to describe a system in terms of its proposed features and the ability to organize agile teams around the features gives us a straightforward method to approach building large-scale systems in an agile manner.

The Feature (Release) Backlog

Returning to the model, we model Features as release level Backlog Items:

Figure 11-Features are another kind of backlog item

At release planning time, Features are decomposed into Stories, which is the team's implementation currency. PlannedFeatures are stored in a Backlog, in this case the Feature (Release) Backlog.

In backlog form, Features are typically expressed in bullet form, or at most, in a sentence or two. For example, you might describe a few features of Google Mail something like:

-

Provide "Stars" for special conversations or messages, as a visual reminder that you need to follow-up on a message or conversation later.

-

Introduce "Labels" as a "folder-like" conversation-organizing metaphor.

Expressing Features in Story Canonical Form

As agilists, however, we are also comfortable with the suggested, canonical Story form described earlier: as a I can so that . Applying this form to the Feature construct can help focus the Feature writer on a better understanding of the user role and need. For example:

As a modestly skilled user, I can assign more than one label to a conversation so that I can find or see a conversation from multiple perspectives

Clearly there are advantages to this approach. However, there is also the potential confusion from the fact that Features then look exactly like Stories but are simply written at a higher level of abstraction. But of course, that's what they really are!

Testing Features

In the team model, we also introduced the agile mantra all code is tested code and attached an Acceptance Test to each Story to enforce that discipline. At the Program level, the question arises as to whether or not Features also deserve (or require) Acceptance Tests. The answer is, most typically, yes. While Story level testing should assure that the methods and classes are reliable (unit testing) and the Stories suits their intended purpose (functional testing), the fact is that a Feature may span multiple project teams and many, many (hundreds) of Stories.

While perhaps ideally, each project team would have the ability to test all Features at the system level, the fact is that that is often not practical (or perhaps even desirable - after all, in the absence of 100% automation, how many teams would we want to continuously test the same feature!). Also, many individual project teams may not have the local resources (test bed, hardware configuration items, other applications) necessary to test a full system. In addition, there are also a myriad of system-level "what if" considerations (think alternate use-case scenarios) that must be tested to assure the overall system reliability; many of these can only be tested at the full system level.

For this reason, Features typically also require one or more functional acceptance tests to assure that the Feature meets the user's needs. To reflect the addition of Acceptance Tests to Features, it is necessary to update the information model with an association from Feature to Acceptance Test as the graphic below shows.

Figure 12-Features have acceptance tests too

In this manner, we illustrate that every Feature requires one or more Acceptance Tests, and a Feature also cannot be considered done until it passes its test.

On System Qualities and Non-functional Requirements

From a requirements perspective, the User Story form and Feature expressions are used to describe the functional requirements of the system; those system behaviors whereby some combination of inputs produces a meaningful output (result) for the user.

With all due respect to that nifty agile invention, however, little has been described in agile as to how to handle the Non-functional Requirements(NFRs) for the system. Traditionally, these were often described as the "ilities" - quality, reliability, scalability, etc. - and served to remind us that these are important and critical elements of system behavior. For if a system isn't reliable (crashes) or marketable (failure to meet some imposed regulatory standard) or scalable (doesn't support the number of users required) then, agile or not, we will fail just as badly as if we forgot some critical functional requirement.

In one perspective, all of these items can be considered to be constraints on new development, in that each eliminates some degree of design freedom on the part of those building the system. For example: "every product in the suite has to be internationalized (constraint), but only the Order Entry module must be localized to Korean (Feature) for this release."

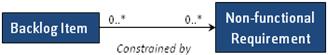

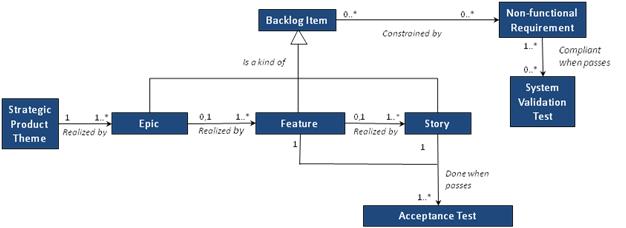

So in the information model, we have modeled them as such:

Figure 13-Backlog items are constrained by Nonfunctional Requirements

We see that a) some Backlog Items may be constrained by zero or more Nonfunctional Requirements (0...*) and b) Nonfunctional Requirements apply to zero or more backlog items (0..*).

Testing Non-Functional Requirements

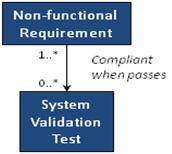

When we look at the long list of list of potential Backlog Constraints - (SCRUPLED: Security, Copyright, Reliability, Usability, Performance, Localization, Essential standards and Design Constraints) - the question naturally arises as to whether these constraints are testable. The answer is mostly yes, as most of these constraints must be objectively tested to assure system quality, as illustrated below:

Figure 14-A system is compliant when it passes System Validation Tests

Rather than calling these tests Acceptance Tests and further overloading that term, we've called them System Validation Tests. This is intended to better describe how this set of tests help assure that the system is validated to be in compliance with its Nonfunctional Requirements. The multiplicity (1..* and 0..*) further indicates that not every NFR has a validation test. However most do (..*) and every system validation test should be associated with some NFR (1..*), otherwise there would be no way to tell whether it passes!

Why the Program Model is Lean and Scalable

Of course, as we scale our model up to the program level, we must constantly check that we are still driving lean, agile and scalable behavior. But indeed we are:

|

It is Still Lean

|

It is Quite Scalable

|

|

Teams apply only the project level story abstractions

|

Features are implemented by stories, and can be traced with tooling

|

|

Features provide a higher level abstraction for program management

|

Higher abstraction simplifies reasoning and assessment for large programs

|

|

Just-in-time feature elaboration eliminates too early requirement specification inventory

|

One Feature backlog can drive Stories for many teams

|

|

Feature backlog construct facilitates system level pull/kanban system

|

Separation of backlogs simplifies administration and tooling

|

The Model for the Agile Portfolio: Strategic Product Themes and Epics

For many software enterprises, including those of modest scope of a few hundred practitioners, the Project Model (primarily Stories, Tasks, and Acceptance Tests) plus the Program Model, (adding Features and Non-Functional requirements) is all that is needed. In these cases, driving the releases with a Feature-based vision and driving iterations with stories that are created by the teams, is as scalable as is required.

However, there is another class of enterprises-enterprises employing many hundreds to thousands of practitioners-wherein the governance and management model for new software asset development needs additional artifacts, and still higher levels of abstraction. In the Big Picture, this is illustrated as the Portfolio level as indicated below:

Figure 15-Portfolio level of the Big Picture

This level introduces two new, additional artifact types Epics and Strategic Product Themes.

Strategic Product Themes

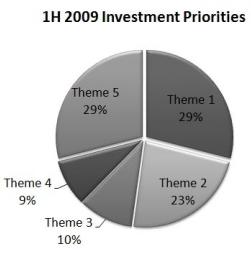

Strategic Product Themes (also called "Investment Themes" or "Themes" for short) represent the set of initiatives which drive the enterprises investment in systems, products and applications. The set of Themes for an enterprise, or business unit within an enterprise, establishes the relative investment objectives for the entity as the pie chart below illustrates:

Figure 16-Strategic Product Themes portfolio mix

These Themes drive the Vision for all product teams and new Epics are derived from this decision. The derivation of these decisions is the responsibility of those who have fiduciary responsibilities to their stakeholders. In most larger enterprises, this happens at the business unit level based on annual or twice annual budgeting process.

Within the business unit, the decisions are based on some combination of:

-

Investment in existing product offerings - enhancements, support and maintenance

-

Investment in new products and services - products that will enhance revenue and/or gain new market share in the current or near term budget period

-

Investment in futures - product and service offerings that require investment today, but will not contribute to revenue until outlying years.

The result of the decision process is a set of Themes - key product value propositions that provide marketplace differentiation and competitive advantage. Themes have a much longer life span than Epics, and a set of Themes may be largely unchanged for up a year or more.

Why Investment Mix Rather than Backlog Priority?

As opposed to Epics, Features and Stories, Investment Themes are not contained or represented in a Backlog (they are not "a kind of Backlog Item") as the model shows.

Figure 17-Portoflio Model adds Epics and Strategic Product Theme

Backlog Items are designed to be addressed in priority order. Strategic Product Themes are designed to be addressed on "a percentage of time to be made available basis." For example, the lowest priority Story on an iteration backlog may not be addressed at all in the course of an iteration and yet the iteration could well be a success (meet its stated objectives and be accepted by the product owner). However, if the lowest priority (smallest investment mix) Strategic Product Theme is not addressed over time, the enterprise may ultimately fail in its mission as it is not making its actual investments based on the longer term priorities it has decided.

Strategic Product Themes also do not share certain other Backlog Item behaviors. For example, as critical as they are, they are not generally testable, as their instantiation occurs first through Epics and then finally, via actual implementation in Features and Stories, which have the specificity necessary to be testable.

Epics

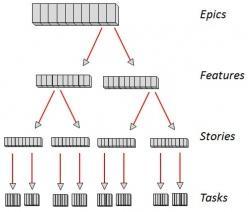

Epic, then, represent the highest level expression of a customer need as this hierarchical graphic shows.

Figure 18-Epics are the highest level requirements artifact

Derived from the portfolio of Strategic Product Themes, Epics are development initiatives that are intended to deliver the value of the theme and are identified, prioritized, estimated and maintained in the Epic Backlog. Prior to release planning3, Epics are decomposed into specific Features, which in turn, drive Release Planning in the Big Picture.

Figure 19-Release Planning in the Big Picture

Epics may be expressed in bullet form, as a sentence or two, in video, prototype, or indeed in any form of expression suitable to express the intent of the product initiative. With Epics, clearly, the objective is Vision, not specificity. In other words, the Epic need only be described in detail sufficient to initiate a further discussion about what types of Features an Epic implies.

Discriminating Epics, Features and Stories

It's apparent by now that Epics, Features and Stories are all forms of expressing user need and implied benefit, but at different levels of abstraction. While there is no rigorous way to determine whether a "thing you know you want to do" is an Epic, Feature or Story, the following table of discriminators should help:

|

Type of Information

|

Description

|

Responsibility

|

Time frame & Sizing

|

Expression format

|

Testable

|

|

Strategic Product Theme

|

BIG, hairy, audacious, game changing, initiatives.

Differentiating, and providing competitive advantage.

|

Portfolio fiduciaries

|

Span strategic planning horizon, 12-18+ months.

Not sized, controlled by percentage investment

|

Any: text, prototype, PPT, video, conversation

|

No

|

|

Epic

|

Bold, Impactful, marketable differentiators

|

Program and product management, business owners

|

6-12 months.

Sized.

|

Most any, including prototype, mockup, declarative form or user story canonical form

|

No

|

|

Feature

|

Short, descriptive, value delivery and benefit oriented statement. Customer and marketing understandable.

|

Product Manager and Product Owner.

|

Fits in an internal release, divide into incremental sub- features as necessary.

Sized in points.

|

Declarative form or user story canonical form.

May be elaborated with system use cases.

|

Yes

|

|

Story

|

Small atomic. Fit for team and detailed user understanding

|

Product Owner and Team.

|

Fits in a single iteration.

Sized in story points.

|

User story canonical form

|

Yes

|

Table 1-Discriminating Themes, Epics, Feature and Stories

OK, the Model is Even Bigger Now, Is it Still Lean and Scalable?

We admit that the model appears to grow in complexity as it scales to the needs of the full enterprise. However, we posit that this is an effect of the complexity of the challenge that the enterprise faces, rather than the model itself, and failure to address this complexity with primary artifacts creates an even more complex model and less lean approach. (Imagine reasoning about 5,000 flat requirements, or 20,000 stories!). So yes, it is still lean, and it is still scalable.

|

It is Still Lean

|

It is Scalable

|

|

Portfolio planners need only two, light-weight, high level abstractions.

|

Portfolio focus on business case and investment mix, rather than system requirements

|

|

There are only a few investment themes at any one time

|

Lighter weight , higher level artifacts simplifies reasoning about large numbers of programs

|

|

There are just a few epics of interest in play at the various program release boundaries

|

Epic-to-feature hierarchy assures investment follows strategic objectives across the full enterprise

|

Summary - The Full Lean and Scalable Requirements Model

In summary, the full lean and scalable requirements model for the agile enterprise appears below.

Figure 20-Full enterprise requirements model

While this model may appear to be more complex that most agilists have typically applied to date, it scales directly to the needs of the full enterprise without burdening the agile teams or adding unnecessary administrative or governance overhead. In this manner, the enterprise can extend the benefits of agility - from the project - to the system - to the portfolio level, and thereby achieve the full productivity and quality benefits available to the increasingly agile enterprise.

Authors: " Dean Leffingwell is an entrepreneur, executive, consultant and technical author who provides product strategy and enterprise-scale agility coaching to large software enterprises. Mr. Leffingwell has served as chief methodologist to Rally Software and formerly served as Vice President of Rational Software, now IBM's Rational Division, where he was responsible for the RUP. His latest book is Scaling Software Agility: Best Practices for Large Enterprises and he is the lead author of the text Managing Software Requirements: First and Second Editions, both from Addison-Wesley. He can be reached through his blog at http://www.scalingsoftwareagility.wordpress.com.

Juha-Markus Aalto is Director, Operational Development of the S60 SW unit of Nokia Devices where he has been leading agile adoption. Mr. Aalto has worked for Nokia for twenty years in various development, quality and leadership positions related to large scale software development. He is one of the authors of the book Tried & True Object Development - Industry-proven Approaches with UML , Cambridge University Press / SIGS Books, 1999."

1 http://scalingsoftwareagility.wordpress.com/category/the-big-picture/

2 Managing Software Requirements: A Use Case Approach. Leffingwell and Widrig. Addison Wesley, 2003.

3 http://scalingsoftwareagility.wordpress.com/category/release-planning/