There is no inherent right or wrong way of writing a problem statement, but a fairly useful and common way is:

- The impact of which is...

- A successful solution would...

So, imagining that we are working for a contact center and there are increasing wait times. The call center manager is keen for us to install a new 'Interactive Voice Response' (IVR) menu system to help route customers to the right location more quickly and to enable them to automatically enter their account information. Yet, this is just one possible solution—and a problem statement might help us to open up the possible solution space. After some discussion and investigation we might settle on:

- The problem of...increasing wait times (particularly those above 30 seconds) on the customer service line

- Is affecting...Customers and contact center staff

- The impact of which is... stress for staff and frustration for customers, leading to decreased staff & customer retention, lower sales volumes and increased complaints

- A successful solution would... Enable existing customers to quickly resolve issues and/or make a repeat purchase, leading to increased customer satisfaction, reduced complaints and higher sales revenues and profits

With problem statements it takes time and iteration to achieve precision and consensus, but this is time well spent. It helps us tactfully nudge our colleagues away from the 'first solution trap'. Stating the problem in solution-agnostic terms helps us foster innovative and divergent conversations about a multitude of options. Indeed, I suspect that when you were reading the problem statement above you were imagining many possible options—increased web presence, process changes, further work to understand any failure demand, as well as changes to the IVR system. In fact, thinking about solutions may lead us to revisit the problem statement and nail it down even further—this is a positive thing.

The problem statement can be incorporated in other documents (for example a Project Charter or Business Case) and will act as a useful guiding beacon throughout the project. When we reach more detail we can ask 'how does this detailed requirement help us solve this problem?'. If it doesn't, perhaps it should be de-scoped... or perhaps the problem space has changed and we need to revisit the purpose and scope of the project! Either way, it is crucial that we know. We may also find that different stakeholders have very different perspectives on the problem: driving these discussions through a problem statement can be an excellent way of highlighting these and working to achieve consensus. It should be noted that, generally speaking a problem statement focusses on the effects rather than the causes of the problem—these can be further examined using a multiple cause diagram as explained below.

Incidentally, if it is an opportunity that is being addressed, the format works equally well:

- The impact of which is...

- A successful solution would...

What Are The Desired Outcomes?

Another important aspect of a problem is to determine 'what will the world look and feel like when it is solved'?, or put differently what

outcomes are we striving for? How will we know when the problem is solved or the opportunity has been leveraged?

When we are involved early in the business change lifecycle it might not be possible to put a number on each of these factors, but defining a scale of measure is still useful. It is useful, for example, to know that the aim is increasing sales revenue in a particular product line. Or reducing administration costs on a particular process.

An extremely valuable tool for eliciting and analyzing these outcomes is the balanced scorecard. I was extremely pleased to see that this well-established technique made it into BABOK® v3. The balanced scorecard, originally conceived by Kaplan & Norton, can be used in many different contexts and at many different levels within an organization. It can be used to set measures that help track success of the entire organization, a department, a project/initiative/change or even a team. When undertaking pre-project problem analysis we'll be concerned with the success of a change—or what BABOK® v3 would call a change strategy.

The traditional balanced scorecard has four dimensions, and encourages us to consider success from multiple dimensions. Although we might immediately focus in on the financial objectives of a project, there may well be others that need consideration too. Indeed, companies that focus too heavily on cost reduction without considering the situation holistically might find that they inadvertently reduce customer service—which has a knock-on negative impact to revenues that they didn't want. Examining the outcomes from varying perspectives helps avoid our stakeholders and us thinking too narrowly.

The traditional four dimensions, with some adaptation, are shown below, with some very high level hypothetical goals/objectives shown:

Area/Explanation

|

Examples of Goals/Objectives

|

Financial

What are the financial outcomes of solving this problem/seizing this opportunity?

|

|

Increased profit

- Increase profit in product line xxx by y% over one year, and z% over three years

And/or

Reduction in processing costs

- Reduction in the cost of processing a sale from $x per sale to $y per sale over one year, with no reduction in sales numbers

|

Customer

What impact will the change have on our customers? How will we measure that impact?

|

Improved customer satisfaction

- Increase in customer satisfaction rating from an average of 70% to 90%, measured by a survey of x customers, within one year

- Increase in net promotor score from x to y within two years

Or

Sustained customer satisfaction

The change is implemented with no negative impact to customer satisfaction, measured by survey and net promotor score

|

Internal Business Process

What internal business processes will we have to monitor or measure in respect of this problem/opportunity?

|

Efficient stock control

- No more than x% 'out of stock' orders within 1 year

And/or

Efficient order picking, packing & dispatch

- x% of orders dispatched within y hours of order

- No more than z% returns due to picking/packing errors

|

Learning and Growth [incorporating "future proofing"]

Traditionally, this element of the balanced business scorecard dealt with learning, growth and innovation. In a project context we can ask what needs to be flexible, and how can we ensure that the organization has adapted (i.e. learned) so that the problem does not occur in the future?

|

Scalability

- The organization, and its underlying systems/processes, shall be able to scale in order to meet the projected increase in business volumes from x to y within z months

|

Figure 1: Examining Goals & Objectives with an Adapted Balanced Business Scorecard

Adapted from Kaplan & Norton (1996)

When eliciting and documenting these high level goals and objectives it is noticeable that there are significant 'grey areas'. For example some financial goals also have a 'customer' element. Many internal business process measures also have a financial element. We should be pragmatic and remember that the technique is useful for prompting us to think about the different areas, and we shouldn't 'force' a fit. Equally, in some contexts it might be appropriate to adapt the dimensions of the balanced business scorecard—particularly where there are different types of 'customer' (take a public sector agency for example, who has one 'customer' (the government) and another (the taxpayer), both of whom have very different measures of success!)

Again, the value in this exercise is both in the discussion with the stakeholders—and the iteration until a consensus is gained—as well as the final documented outcome.

What Is The Current State? Understanding the Problem (And Its Root Causes)

With a completed problem statement and balanced business scorecard, we have a very good understanding of the

scope of the problem and

why it would be desirable to solve it. Yet we haven't yet delved into the problem-space itself. Unless we are starting from a completely blank canvas, there will be an existing set of processes and systems interacting to deliver services, intermingled with a wide range of stakeholders. Disentangling the problem from its cause or causes can be challenging.

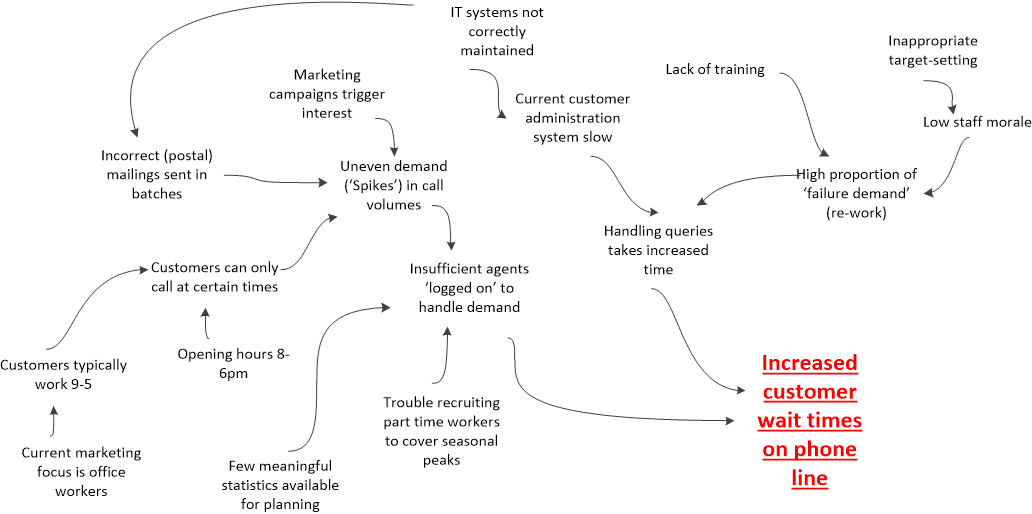

One technique that we can use is the fishbone diagram, this helps us to consider a problem from a range of dimensions, and how varying causes might impact us. However, an alternative technique that can work particularly well for very messy and tricky problems is a multiple cause diagram. This diagram is utilized within the systems thinking and systems practice arenas, and is equally well suited to business analysis. A multiple cause diagram requires very little (if any) explanation, so I have included an example below:

Figure 2: Multiple Cause Diagram (Example)

This partial example shows how the richness of a problem (and its causes) can be represented. We might often start with a suspicion that the cause of the problem originates from one area, only to find that there are many others too. In these cases it can be useful to denote scope on a multiple cause diagram, by indicating which elements of a problem are considered candidates for further examination (either by color coding or by drawing a boundary of scope). This also helps us bring any potential differing or competing perspectives forward, so that we can discuss and reconcile them early (before the project gets going).

As you can see, conceptually this type of diagram has similarities with a fishbone diagram, but it is a more fluid form. Of course, we are not restricted to using one or the other in our analysis—these are just two potential tools in our toolbox. We might use either, both, or something different! I often find I start out with one technique in mind but then adapt when I find that the problem is simpler/more complex than I first thought. This ability for us to adapt to our context, and draw from a wide range of tools, is what makes business analysis such a fascinating career (in my opinion at least!).

Conclusion

As BAs we can add a huge amount of value throughout the business change lifecycle, and we can add value inside and outside of projects. We have a rich and varied toolkit, and this article has summarized just a few techniques that I hope you'll find useful.

Author: Adrian Reed, Principal Consultant and Director at Blackmetric Business Solutions

Adrian Reed is a true advocate of the analysis profession. In his day job, he acts as Principal Consultant and Director at Blackmetric Business Solutions where he provides Business Analysis consultancy and training solutions to a range of clients in varying industries. Adrian is a past President of the UK chapter of the IIBA® and he speaks internationally on topics relating to Business Analysis and business change. You can read Adrian's blog at http://www.adrianreed.co.uk. Follow Adrian on Twitter @UKAdrianReed.

Readers of this article may also be interested in Adrian’s 2015 book ‘Be A Great Problem Solver…Now!’

References & Further Reading

Kaplan, R. and Norton, D. (1996). The Balanced Scorecard. 1st ed. Boston, Mass: Harvard business school press.

IIBA®, (2015). Guide to the business analysis body of knowledge (v3). Toronto : Ontario: International Institute of Business Analysis.