Business process models are intuitive. That’s why people like them. They provide management blueprints for coordinating repetitive work. But are they sufficient for creating an optimal business solution for a business challenge? No. This discussion brings into focus some of their blind spots and what you can do to address them successfully.

| Excerpted with permission from Building Business Solutions: Business Analysis with Business Rules, by Ronald G. Ross with Gladys S.W. Lam, An IIBA® Sponsored Handbook, Business Rule Solutions, LLC, 2011, 304 pp, http://www.brsolutions.com/bbs |

The best definition of business process I have come across to date is Janey Conkey Frazier’s from one of the very first Business Rule Forum conferences in the late 1990s: the [business] tasks required for an enterprise to satisfy a planned response to an operational business event from beginning to end with a focus on the roles of actors, rather than the actors’ day-to-day job.

I especially like that part about a planned response to an operational business event. It raises a very interesting question: Can you possibly predict all the operational business events that might happen in your business and all the circumstances under which those operational business events might occur? What do you do about the ones you can’t predict? Be thinking about those questions. I’ll come back to them later.

The key word in understanding business processes is transformation. A business process takes operational business things as inputs and transforms them into outputs. These outputs might be the same operational business things in some new state, or altogether new operational business thing(s). For example, a business process might take raw materials and transform them into finished goods. A successful transform creates or adds value, though not always in a direct way.

Collectively, the boxes and arrows in a business process model represent management’s blueprint for understanding, coordinating, and revising how operational work in the organization gets done – that is, how value add is created. Consequently:

-

Responsibility for performing business tasks can be re-allocated (or automated) as appropriate.

-

Bottlenecks can be identified and corrected.

-

Appropriate business rules can be applied to ensure work is done correctly.

|

Is There Always a Process?

A restaurant sometimes allows members of a party to split the bill for a meal so each person can pay just part.

Business Rule: The amount paid for a meal may be split among the members of the party served the meal only if all the following are true:

- Each member initials his or her portion of the amount paid on the bill for the meal.

- Each member provides the room number in which he or she is currently registered in the hotel.

Does the restaurant have some business process for collecting payment? Of course. The bill for meals usually does get paid (usually involving a transform of my personal financial resources!). But that’s not the right question.

The real question is whether the business process is simply ad hoc, or modeled and prescribed (or somewhere in between). No matter, the business rule always applies. That’s important because there will always be at least some ad hoc business activity – and perhaps quite a lot.

|

How Does Strategy Fit?

Often, initiatives featuring business process models start off great guns. Everyone is excited to be involved and to see some ‘big picture’ emerge, possibly for the first time. Things go well for a while but then start to bog down, sometimes fatally. Why? There are many reasons, but three stand out that you can do something about.

-

Business rules are embedded in the flows. Just don’t do it. It won’t scale. As you consider and incorporate more and more scenarios, the complexity of the business process model compounds itself. As business people mentally drop out, IT takes the helm. Not what you want!

-

Organizational politics kick in. Managers start silently assessing what the emerging to-be model means to their area’s head count and budget. If they feel they’re likely to lose out, they understandably start to politically drop out. To counteract this response as soon as it kicks in, something needs to be already in place.

-

Unanswered questions surface about critical business practices and trade-offs. Such questions typically pertain to tricky or risky or difficult scenarios. Maybe black swans. Maybe day-to-day operational issues. Maybe showstoppers. Since you probably started modeling with the happy path (recommended), little or no thinking may have been devoted to these other issues.

The solution to the last two problems is to create a strategy for the business solution (we call the deliverable a Policy Charter) before you start modeling the business process(es). Without a strategy to address significant business risks and set key business policies, it’s hardly a surprise things can go awry. In essence, you’re trying to develop a management blueprint for how work is done without having established key parameters about the shape of the business solution.

| A Father’s Story

My three children are grown now, but when they were young, Friday was ‘pancake night’ at IHOP, our family’s special time just to talk. The kids would discuss whatever was happening at school or with sports and friends (and, of course, video games). I would talk about work some. Really! Sometimes I would even try out new lecture material. Kids are just full of surprising responses.

In those days, Gladys Lam (co-founder of Business Rule Solutions, LLC) and I had just started doing Policy Charters. We often used a pizza business as a case study. I told my kids the pizza business wanted to deliver pizzas within five minutes. I thought it would stump them.

“No problem!” they cried. “We’ll operate a fleet of helicopters 24x7 with radio dispatch. We’ll put the ovens right on board the helicopters [big helicopters!], all the ingredients, everything, so as soon as we get an order we’ll send the helicopter right toward the person’s house. We’ll bake the pizza in route … and check their credit, of course. After all, we do want to get paid for that $15[!] pizza. Upon arrival, the customer can come out into their front yard [where we live, everybody has yards] and we’ll parachute the pizza down to them.” Then my older son (now a lawyer) spoke up, “And we’ll get liability insurance in case the parachute doesn’t open and the pizza hits them on the head and knocks them out.”

Then I radically changed the business policy: Pizzas must be delivered within seventy-two hours. They weren’t nearly as interested in that one. They said, “Aw, we’ll just mail them the pizza!”

Then I set the business policy to within one hour. I should have known what was coming. Almost immediately they launched into when they would be getting their own cars. Wouldn’t I be just so pleased they could earn money by delivering pizzas in their own cars as soon as they started driving?! (Not!)

The serious point behind the story is this. The process of flying helicopters to deliver pizzas is very different from handing off pizzas to the postal service, which is very different from dispatching owner-operated vehicles. Until you establish the basic business policies, how can you model the business process?!

|

The content of the Policy Charter helps shape the business process model in at least three specific ways.

Business tasks that need to be done. Suppose the Policy Charter includes the business policy: A receipt should be given to a customer for every purchase. This business policy addresses three business goals: to facilitate return of goods, to keep the customer satisfied, and to minimize insider theft. The implication is that a business task Generate receipt needs to be included in the business process model.

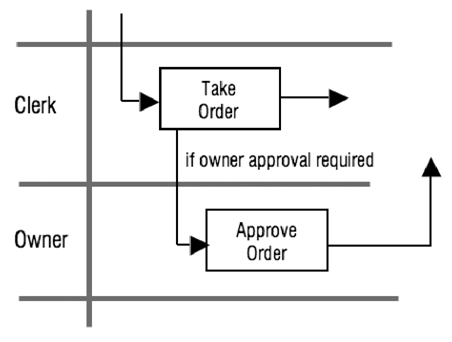

Allocation of responsibility to actors. Suppose the Policy Charter includes the business policy: An order that exceeds the customer’s credit limit by more than $50,000 must be approved by the owner. This business policy addresses two business goals: to minimize financial exposure and to encourage large sales. (The customer might be an old golf buddy of the owner.) The implication is that the business task Approve order must be assigned to the actor owner (e.g., included in the owner’s swim lane).

Evaluation of conditionals. Suppose the Policy Charter includes the following three business policies: (1) An order that exceeds the customer’s credit limit by more than $50,000 must be approved by the owner. (2) An order that exceeds the credit limit of a long-time customer must be approved by the owner. (3) A rush order placed by a new customer not yet given a credit limit must be approved by the owner. In Figure 1, these business policies determine when a case is to follow the conditional flow if owner approval required between the business task Take order and the owner’s business task Approve order.

Figure 1. Conditional Flow in a Business Process Model

The Issue of Completeness

A common device used in modeling business processes is scenarios, which assist with:

Can a business process model (or set of them) ever really be complete? Earlier I asked whether you can possibly predict all the operational business events that might happen in your business and all the circumstances under which those operational business events might occur. You obviously can’t. You could model scenarios from now until you retire and still probably not cover them all.

A key question then is which scenarios should you model, and which ones not? Generally, you should probably model a scenario if it’s high frequency or involves a large number of employees doing the same kind of work. You probably shouldn’t if it’s low frequency and involves only a small number of employees.

That answer is more subtle than it seems. Suppose the large majority of claims submitted to an insurance company are for less than $10,000. One day a claim arrives for $10,000,000 (fortunately, a very rare event). Only a few people in the whole company are qualified to handle such a claim.

So should you model that rare scenario? What happens to scenarios left un-modeled?

A claim of such magnitude clearly presents a significant business risk to the insurance company. Where are such risks addressed? The Policy Charter. Appropriate business policies should have already been developed to protect the company. A business process is not the answer. You need a good strategy for the business solution!

If you develop strategy beforehand, and then specify all the know-how separately as business rules, what does a business process model really do for you? Think back to the earlier definition of business process, which described it as a planned response to an operational business event. That’s spot on. A business process model is a management blueprint that that provides a focal point for coordinating highly repetitive work.

Author: Ronald G. Ross is recognized internationally as the ‘father of business rules.’ He is Co-founder and Principal of Business Rule Solutions, LLC, where he is active in consulting services, publications, the Proteus® methodology, and RuleSpeak®. Mr. Ross serves as Executive Editor of BRCommunity.com and as Chair of the Business Rules Forum Conference. He is the author of nine professional books, including his latest, Building Business Solutions: Business Analysis with Business Rules with Gladys S.W. Lam (2011, http://www.brsolutions.com/bbs), and the authoritative Business Rule Concepts, now in its third edition (2009, http://www.brsolutions.com/b_concepts.php). Mr. Ross speaks and gives popular public seminars across the globe. His blog: http://www.ronross.info/blog/ . Twitter: Ronald_G_Ross

Author: Ronald G. Ross is recognized internationally as the ‘father of business rules.’ He is Co-founder and Principal of Business Rule Solutions, LLC, where he is active in consulting services, publications, the Proteus® methodology, and RuleSpeak®. Mr. Ross serves as Executive Editor of BRCommunity.com and as Chair of the Business Rules Forum Conference. He is the author of nine professional books, including his latest, Building Business Solutions: Business Analysis with Business Rules with Gladys S.W. Lam (2011, http://www.brsolutions.com/bbs), and the authoritative Business Rule Concepts, now in its third edition (2009, http://www.brsolutions.com/b_concepts.php). Mr. Ross speaks and gives popular public seminars across the globe. His blog: http://www.ronross.info/blog/ . Twitter: Ronald_G_Ross