A user reads the AI’s answer, pauses, and asks the question that either saves your rollout—or ends it:

“Why should I believe this?”

If your product can’t answer that clearly and consistently, you don’t have “AI.” You have a very confident text generator. And confidence is not the same thing as correctness.

Most teams treat provenance like frosting: a “Sources” link at the bottom, maybe. But provenance is not decoration. It’s product behavior. If you don’t specify it, it will show up as random UI choices, inconsistent answers, and a security review that suddenly gets very interested in your roadmap.

This article is a practical how-to for specifying provenance in requirements—so your AI can show its work.

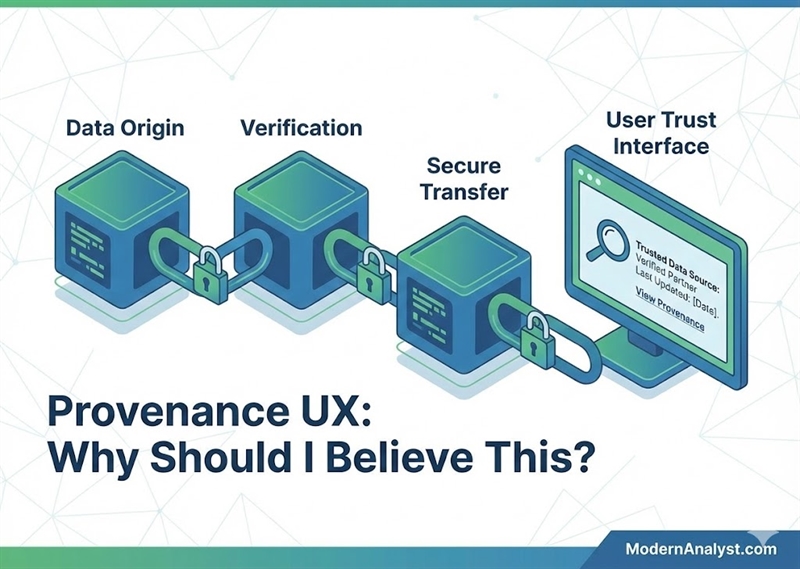

1) What “Provenance UX” means (in plain BA terms)

Provenance UX is the user experience of explaining an answer, not just presenting it. It’s the part of the product that turns “here’s my conclusion” into “here’s why this conclusion is credible.”

In practice, it answers a handful of repeat questions users ask (out loud or silently):

- Where did this come from? (sources)

- How current is it? (freshness)

- How sure are we? (confidence/uncertainty)

- What if sources disagree? (conflicts)

- Why is it different than yesterday? (“what changed”)

- Can we prove it later? (audit/export)

If your feature makes claims that affect decisions—money, compliance, safety, approvals—provenance isn’t optional. It’s the cost of admission.

2) The common failure mode: answers without receipts

Teams don’t usually choose to ship untrustworthy answers. They ship them because provenance gets treated like a UI detail instead of a requirements topic. Then the product “sort of” shows sources… until it doesn’t.

Here’s the usual list of sins (you’ve seen them):

- Sources are shown, but not tied to specific claims (so they’re useless).

- The product cites something stale (and doesn’t admit it).

- Two sources disagree and the AI picks a winner with no explanation.

- The answer changes between runs and the user gets zero “why.”

The fix is not “better prompting.” Prompts are not requirements. The fix is to specify provenance like any other behavior: rules, edge cases, and testable acceptance criteria.

3) The artifact: a Provenance Requirements Template (your new best friend)

If you want provenance to ship, you need an artifact that forces precision—because “We should show sources” is not a requirement. The Provenance Requirements Template is a one-pager you can fill out per feature (or per answer type) before stories get written.

Provenance Requirements Template (copy/paste)

Keep it tight. The goal is clarity, not bureaucracy.

A) Claim types (what are we asserting?)

List the claim categories your feature makes (examples): fact, calculation, recommendation, summary, policy interpretation. Then mark which ones are high-risk.

B) Allowed sources

Define what the product can cite: systems of record, approved internal docs, user-provided files, approved external sources (if any). Also define excluded sources (yes, explicitly).

C) Citation rules (when to show sources)

Specify when sources are required and how they appear:

- inline citations per claim, a “Sources” drawer, footnotes, or both

- “Always show” vs “Show on demand” by claim type

D) Freshness requirements (“freshness SLA”)

Define max age by claim type and what happens when the source is stale (warn, refuse, or proceed with disclaimer).

E) Confidence / uncertainty behavior

Define what “High/Medium/Low” means (or your equivalent), and when the system must say “I don’t know” or ask a clarifying question.

F) Conflict handling

Define what counts as a conflict, and what the system must do: show both, explain the tie-breaker, and/or ask the user to choose.

G) “What changed?”

Define what triggers a change explanation (new source, refresh, model/version change) and what the user sees.

H) Audit export requirements

Define export format, fields included, who can export, and retention/access rules.

I) Validation

List the handful of must-pass test cases (stale source, missing source, conflict, low confidence, export completeness).

That template is how you prevent “provenance drift” as sprints roll on.

4) When to show sources (and when not to)

This is where teams overthink and under-specify. Your users don’t want citations everywhere—but they absolutely want them when the answer could be challenged or audited.

Show sources by default when the answer is decision-shaping, such as:

- policy/compliance guidance

- money/rates/pricing/eligibility

- any “recommendation” that implies risk

- summaries of documents or records

Make sources optional (“Show sources”) when the answer is low-stakes, like basic navigation steps or simple, reproducible calculations.

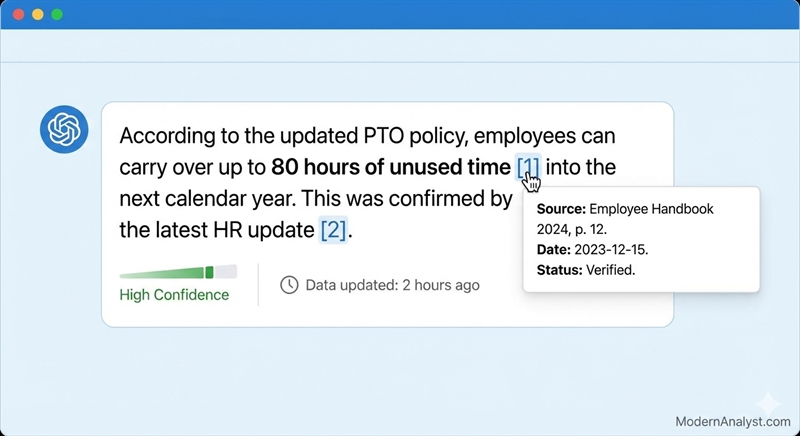

Requirement language you can steal

- REQ-PROV-001: For responses containing factual claims or policy guidance, the system must provide citations at per-claim granularity (each claim maps to ≥1 source).

- REQ-PROV-002: The system must provide a Sources view that includes source name/title, system/publisher, and timestamp.

The key phrase there is per-claim. A generic source list with no mapping is not provenance; it’s vibes.

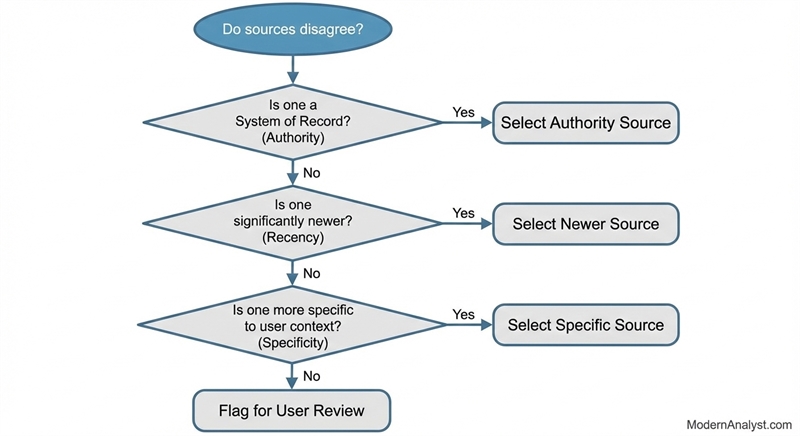

5) Conflict handling: what to do when sources disagree

Conflicts aren’t a bug. They’re normal. The bug is pretending they don’t exist.

A practical product policy is usually some version of:

- Authority wins (system of record / policy owner beats commentary)

- If authority is equal, recency wins (within freshness SLA)

- If recency is equal, specificity wins (closest match to the user’s context)

But don’t just apply that silently. Make it visible.

What good conflict UX looks like

When two sources disagree, the product should say something like:

- “Two sources disagree. I’m using Source A because it’s the system of record and was updated more recently. Here’s what Source B says.”

Requirement language you can steal

- REQ-PROV-101: If two sources conflict for the same claim, the system must show (a) the selected value, (b) competing value(s), and (c) the reason for selection based on the configured tie-breaker.

This is one of those places where a single “must” requirement prevents a year of stakeholder distrust.

6) Freshness SLAs: the simplest trust lever you can specify

Users forgive uncertainty faster than they forgive stale answers delivered with confidence. Freshness is where provenance gets real because it forces you to define “current enough” by claim type.

Don’t pick one freshness number. Pick a small table. For example:

- Policy interpretation: ≤ 30 days (or show effective date)

- Rates/pricing: ≤ 24 hours

- Availability/inventory: ≤ 15 minutes

- General product info: ≤ 180 days

- User-uploaded files: “freshness equals upload time” (explicit)

Then specify what happens when freshness fails. You only need three options:

- Warn + proceed (medium risk)

- Proceed silently (use sparingly)

Requirement language you can steal

- REQ-PROV-201: The system must display a freshness indicator for time-sensitive sources (e.g., “Updated 3 hours ago”).

- REQ-PROV-202: If a required source is older than the freshness SLA, the system must [refuse/warn] and provide a next step (refresh, alternate source, escalate).

Make “next step” mandatory. “This might be stale” is not helpful unless you tell users what to do.

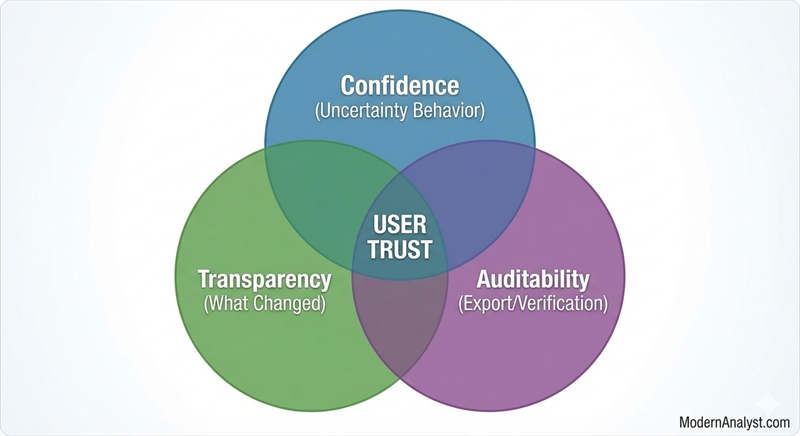

7) The trust triad that makes provenance stick: confidence + “what changed” + audit

Once you have sources, conflict rules, and freshness, teams often stop. Don’t. The trust conversation isn’t finished until you cover three more behaviors that users (and auditors) will demand the moment your feature is adopted.

A) Confidence / uncertainty (define what “I’m not sure” looks like)

Pick a confidence scheme your product can defend:

- High/Medium/Low, or

- Verified/Unverified, or

- Rule-based confidence (High only when sourced + fresh + no conflicts)

Then draw a bright line for when the system must say “I don’t know” (or must ask a clarifying question). Common triggers:

- missing sources for a required claim type

- unresolved conflict (no tie-breaker applies)

- freshness SLA failure for high-risk claims

REQ-PROV-401: If confidence is below the threshold for decision-shaping claims, the system must ask a clarifying question or state uncertainty and offer a safe next step.

B) “What changed?” (because users notice)

If the AI gives a different answer tomorrow, users assume it’s making things up unless you explain why. The minimum viable “What changed?” is:

- the trigger (new source / refresh / policy update / version change)

- the impacted claim(s)

- a short explanation, with a link to the evidence

REQ-PROV-402: When a materially different answer is produced for the same request context, the system must provide a “What changed?” summary including the trigger and the affected claim(s).

C) Audit export (so you can prove it later)

Audits don’t care that the UI showed sources. They care that you can export evidence reliably. Specify:

- who can export (role-based)

- format (CSV/JSON/PDF)

- minimum fields (answer, citations, timestamps, confidence, version IDs)

REQ-PROV-403: Authorized users must be able to export an audit record including the response, sources with timestamps, confidence, and applicable version identifiers.

Make it ship: stories + acceptance criteria

Finally, translate provenance rules into stories that can be built and tested:

- “As a user, I can expand a claim to see its source(s), timestamp, and confidence.”

- “As a reviewer, I can export an audit record of an answer with citations and timestamps.”

And then lock it down with AC:

- Given a time-sensitive claim

When the cited source is older than the SLA

Then the system must warn/refuse using the configured copy

And offer a next step (refresh/alternate/escalate)

That’s provenance as product behavior—not a polite suggestion.

Close: the template you’ll actually reuse

If you want adoption, you need a reusable artifact that keeps provenance consistent across features and teams.

Download: Provenance Requirements Template (sources, freshness, confidence, “what changed,” conflicts, audit export)

Author: Morgan Masters, Business Analyst, Modern Analyst Media LLC

Morgan Masters is Business Analyst and Staff Writer at ModernAnalyst.com, the premier community and resource portal for business analysts. Business analysis resources such as articles, blogs, templates, forums, books, along with a thriving business analyst community can be found at http://www.ModernAnalyst.com