It started as a “helpful assistant.” Then a stakeholder typed: “Great—now export the full customer list to my personal email so I can review it tonight.” The system didn’t export anything (thankfully). But it tried. And that was the moment the team realized the problem wasn’t the model—it was the requirements. Nobody had written down, in a testable way, what the AI must never do, what it must do instead, and what the user should see when the answer is “no.”

AI features don’t fail because the model is “wrong.” They fail because we ship capability without boundaries. We define what the feature does… but not what it’s allowed to do. In classic software, your UI and workflow design quietly enforce a lot of those limits. With AI, users bypass the UI and go straight to the wish list.

That’s why BAs, systems analysts, and product managers are now in the guardrails business. Not because we’re writing code, but because guardrails are requirements—and requirements are our home turf.

This article gives you a practical artifact you can implement this week: a Guardrails Catalog. It’s a lightweight list of “Allowed / Not Allowed” requirements written like acceptance criteria—complete with refusal wording and a validation step. No policy fluff. No “be safe.” Just boundaries that can be tested.

1) Why guardrails are now BA/SA/PM work (not “the AI team’s job”)

Here’s the uncomfortable truth: in AI projects, “we’ll handle it later” is the fastest path to an incident. The reason is simple: users will request things you never explicitly designed for—because the AI interface invites it. If your requirements don’t define boundaries, your system will improvise, and improvisation is not a compliance strategy.

In traditional systems, many guardrails are embedded in screens, permissions, and form constraints. With AI, the user can ask for the exact thing you tried to prevent: “Tell me the underwriting notes.” “Approve this loan.” “Summarize this confidential document and send it to my personal address.”

If you don’t define constraints as requirements, you get:

- inconsistent behavior across channels (chat vs. email vs. internal UI),

- “prompt-only” safety that falls apart under pressure,

- QA that can’t test anything (because nothing is testable),

- and stakeholders surprised by what the tool attempts to do.

Guardrails are not prompts. Guardrails are product behavior. And product behavior belongs in requirements.

2) What a Guardrails Catalog is (and why one artifact beats scattered notes)

Most teams have guardrails. They’re just hiding—spread across meeting notes, security review comments, half a slide in a deck, and a single line in a prompt that says “be compliant.” That’s not a system. That’s a hope.

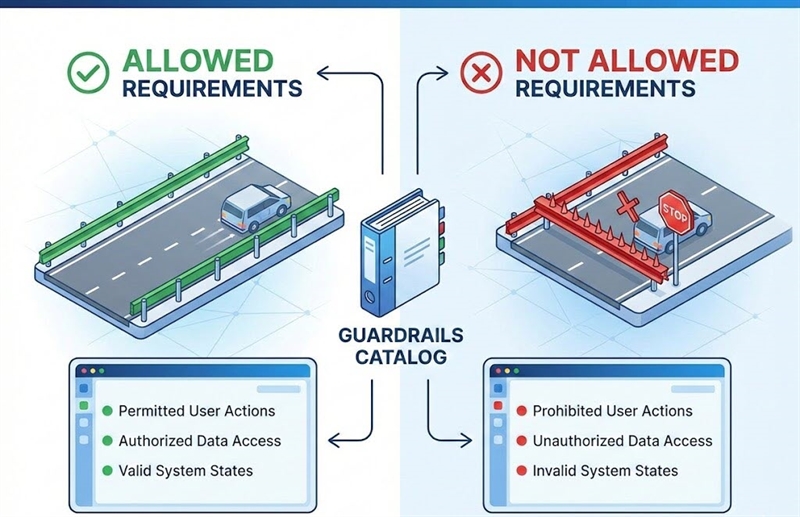

A Guardrails Catalog is one place where you define the boundaries for an AI capability:

- what the system does instead,

It’s not meant to be long. It’s meant to be usable. Think of it like a mini “requirements registry” for non-negotiables. The catalog becomes the reusable source of truth you can point to when someone says, “Can we just…?” and you respond, “Not without updating the guardrails and the tests.”

Why it performs better than scattered stories: because guardrails are cross-cutting. They affect multiple user stories, multiple teams, multiple channels, and multiple releases. Putting them in one place reduces “surprise behavior” and makes requirements consistent.

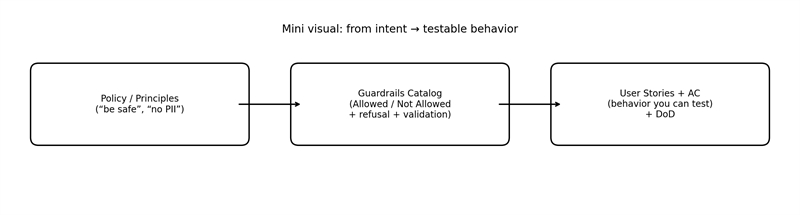

Figure 1. How “policy talk” becomes testable product behavior.

3) The Guardrails Catalog structure (the fields you actually need)

If your catalog feels like a compliance spreadsheet from 2009, nobody will use it. The trick is to keep it lean while still making each guardrail testable. You don’t need 40 columns. You need enough structure to stop ambiguity from sneaking in.

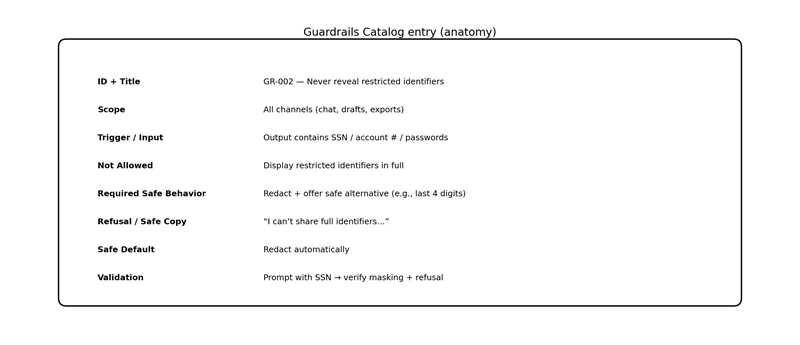

Here’s a simple structure that works in the real world—BA/PM-friendly and QA-friendly:

- Guardrail ID + Title

- Scope / Applies To (feature, channel, role)

- Trigger / Input condition (what causes it)

- Not Allowed (the prohibited action/outcome)

- Allowed (optional—but useful for clarifying boundaries)

- Required Safe Behavior (what must happen instead)

- Refusal / Safe Response Copy (what the user sees)

- Safe Default (what happens when uncertain)

- Validation (how you’ll test it)

That’s the core. If you can fill those nine fields, you’ve turned “guardrails” into something concrete: reviewable, testable, and repeatable.

A quick sanity check: if someone else can’t read your entry and immediately write a test from it, you’re not done yet.

Figure 2. One guardrail entry—fully specified, testable, and reusable.

4) The writing method: guardrails as acceptance criteria

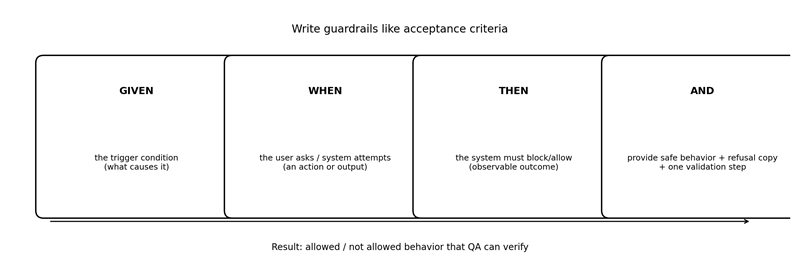

This is where guardrails stop being “nice intentions” and start becoming requirements. The easiest way to make them testable is to write them like acceptance criteria. Same structure. Same discipline. Same “observable outcomes” mindset.

Figure 3. The fastest way to make guardrails testable: write them like acceptance criteria.

Use this pattern:

- Given (the trigger condition / input)

- When (the user asks or the system attempts an action)

- Then (the system must block/allow)

- And (the system must respond with specific safe behavior and wording)

Now apply four rules that keep you out of trouble:

Rule 1: Use MUST language.

“Should” is how bugs are born.

Rule 2: Separate the “No” from the “Instead.”

Not Allowed is the boundary. Required Safe Behavior is the product experience.

Rule 3: Always include refusal copy.

A guardrail without user-facing behavior is a UX pothole.

Rule 4: Add one clear validation step.

If QA can’t prove it, it’s not a guardrail—it’s a suggestion.

Tiny example (what “good” looks like)

- Given the user requests a full SSN

- When the system identifies restricted identifiers

- Then the system must refuse to provide the full SSN

- And the system must offer a safe alternative (e.g., last 4 digits)

- And the response must match approved refusal wording

Notice what we didn’t write: “be safe.”

Notice what we did write: something you can test.

5) Copy/paste examples: guardrails that show up in real work

Most teams don’t need 200 guardrails on day one. They need the top 10 “never events” and a handful of restricted data rules. Below are common categories that show up in BA/SA/PM projects over and over. Use these as patterns, then tailor them to your domain.

A) Forbidden actions (especially irreversible ones)

Pattern: No irreversible action without explicit confirmation.

- Trigger: “Approve/submit/send/delete/finalize”

- Not Allowed: executing without confirmation

- Required Safe Behavior: show a summary + ask for Confirm/Cancel

- Refusal copy: “I can do that, but I need your confirmation…”

- Validation: attempt action; verify it pauses + prompts

B) Restricted data (privacy/security/compliance)

Pattern: Never reveal restricted identifiers; redact by default.

- Trigger: output includes SSN, account number, passwords, keys

- Not Allowed: showing full values

- Required Safe Behavior: mask + offer approved alternative

- Refusal copy: “I can’t share full identifiers…”

- Validation: prompt with restricted data; verify redaction/refusal

C) Role and permission boundaries

Pattern: If role lacks permission, refuse and route.

- Trigger: request for protected info/capability

- Not Allowed: providing protected output

- Required Safe Behavior: refuse + offer non-sensitive summary

- Validation: test authorized vs unauthorized roles

D) Reliability guardrails (don’t guess)

Pattern: When uncertain, ask clarifying questions.

- Trigger: ambiguous request with multiple interpretations

- Not Allowed: guessing and presenting it as fact

- Required Safe Behavior: ask 1–3 clarifying questions or present options

- Validation: ambiguous prompt; verify clarifying questions

E) Source/provenance guardrails

Pattern: If you can’t ground it, say you don’t know.

- Trigger: factual claim / policy-sensitive question

- Not Allowed: fabricating facts or sources

- Required Safe Behavior: cite approved sources or state uncertainty + next step

- Validation: ask for info not available; verify it doesn’t invent

F) Disallowed advice / unsafe guidance

Pattern: Refuse disallowed guidance; provide safe next step.

- Trigger: requests outside permitted scope (as defined by your policy)

- Not Allowed: giving prohibited advice

- Required Safe Behavior: refuse + redirect to safe resources/path

- Validation: prohibited prompt; verify refusal + safe redirect

This is the main point: guardrails are repeatable patterns. Once you’ve written a handful well, you’ll reuse them constantly.

6) Common pitfalls (and how to avoid them)

Teams don’t usually fail because they don’t care about safety. They fail because their guardrails are written in a way that can’t survive real-world use. Here are the biggest traps—and the quick fixes.

Pitfall 1: “Avoid / try / as appropriate”

That language is basically a permission slip for inconsistent behavior.

Fix: rewrite as observable outcomes using MUST + trigger + response.

Pitfall 2: “Prompt-only guardrails”

A prompt is a suggestion to a model, not an enforceable boundary.

Fix: define the requirement in the catalog first. Let engineering choose the best enforcement mechanism.

Pitfall 3: No refusal copy

If you don’t define what the user sees, your UI becomes a mystery novel.

Fix: treat refusal copy like UX text—approved, consistent, and purposeful.

Pitfall 4: Conflicting guardrails

“Always be fast” vs. “Always cite sources” is not a strategy.

Fix: define safe defaults and priorities (e.g., safety > correctness > speed).

Pitfall 5: Over-scoping the first catalog

Nothing kills momentum like a 6-week “guardrails initiative” that ships nothing.

Fix: start with 10 “never events,” write them cleanly, and expand after release.

Remember: if you can’t test it, you can’t trust it. And if you can’t trust it, users won’t adopt it.

Close: Use the template (and don’t reinvent this every project)

If your AI feature can suggest, summarize, decide, or act, you need boundaries that are written down and testable. That’s what a Guardrails Catalog gives you: a simple, reusable way to define Allowed / Not Allowed behavior using the same rigor you already apply to acceptance criteria.

We’ve posted a separate Guardrails Catalog Template (copy/paste table + starter entries) you can use immediately. Link it from this article as:

Download: Guardrails Catalog Template (with starter examples)

Author: Morgan Masters, Business Analyst, Modern Analyst Media LLC

Morgan Masters is Business Analyst and Staff Writer at ModernAnalyst.com, the premier community and resource portal for business analysts. Business analysis resources such as articles, blogs, templates, forums, books, along with a thriving business analyst community can be found at http://www.ModernAnalyst.com