Business analysts possess special capabilities that enhance their value to any team or organization.

AI image generated by the author at Craiyon

Business analysis is now recognized as a profession, complete with bodies of knowledge, certifications, and respect. While BAs typically perform software requirements activities, their work can extend to many other aspects of assessing an organization’s needs and the characteristics solutions must possess to meet them. It’s not an easy job.

Whether they entered the profession with a background in software, as a user, or from some other position, effective BAs share several characteristics. They possess knowledge, skills, tools, and personality traits that let them make significant contributions to project and product teams. Maybe they can’t leap tall buildings in a single bound, but a strong BA has five superpowers that can add value to any initiative or organization.

Superpower #1: Creating Order from Chaos

I’m pretty good at organizing messy situations. Reducing disorder is a major BA superpower. Business analysts are skilled at seeing patterns, grouping related items, and managing complexity through hierarchies. Creating that organization helps reveal missing, duplicated, erroneous, and unnecessary business functions and solution requirements.

Stakeholders are likely to bombard you with random input. You’ll hear user tasks, scenarios, business objectives, functional requirements, data objects, constraints, business rules, product features—and extraneous information. It’s challenging to work with a brain dump like that.

The BA needs to classify each bit of information, spot relationships, and organize everything into a manageable set that speaks to a variety of stakeholders. BAs use templates and visual models to put each piece of knowledge in a sensible place and create a workable basis for solution development. When faced with chaos, some people are so trapped in the weeds that they don't know where to start. The solution is to move up a level to see it all, and then classify, organize, and document.

As an example, a stakeholder presented an experienced BA with a large set of requirements that lacked organization. The BA couldn’t quite make sense of them all. He decided to create a mind map to bring some structure and hierarchy to the pile. The stakeholder was delighted by the clarity the mind map provided.

Superpower #2: Asking the Right Questions

Preventing a mess in the first place is even better than cleaning it up. Skillful BAs don’t start by asking stakeholders “What do you want?” or “What are your requirements?” They begin with questions to understand why the organization is undertaking the initiative. What problem do they want to solve, or what opportunity do they wish to exploit? Is the presented problem the real problem? (Use root cause analysis.) What’s the organization hoping to accomplish? (Create a business objectives model.)

Once they establish that business foundation, the BA might ask representative users, “What do you need to do with the solution?” It’s more effective to focus requirement explorations on usage than on product features. This is a challenge because most stakeholders begin with the solution they already have in mind. The discussion continues with questions to reveal the breadth and depth of the needs, and then explores the solution’s necessary capabilities and characteristics. Asking “Why?” often leads to a more accurate and more thorough understanding.

The BA is not simply a scribe, recording whatever various stakeholders tell them. An effective BA probes below the surface, seeking the unstated:

- If you hear an assumption, is it still valid? Says who? What if it’s not?

- If you hear a solution idea, is it a true constraint or just an idea?

- Who needs the capability a user just described?

- Is there any other way that a user might want to perform a particular task?

- What constraints, standards, regulations, and policies must the solution respect?

- How should the solution handle various error conditions?

- When someone says “user-friendly,” what do they mean? How could we assess that? Ditto for many other quality attributes.

No, the BA is not a scribe but an explorer, guiding the development team to solve the right problem by building the right functionality correctly at the right time. The BA keeps stakeholders from wandering around aimlessly, albeit with the best of intentions.

As organizations begin to use AI to help generate product requirements, a savvy BA provides a critical reality check. Generative AI tools are well known for creating hallucinations, erroneous or made-up content that is presented just as authoritatively as accurate information. The BA should validate whatever the AI creates, rather than simply assuming it’s all correct. Don't expect AI to replace solid critical thinking.

Superpower #3: Moving Between Abstraction Levels

Some folks are big-picture people (high abstraction level). Others prefer to focus on the details (low abstraction level). However, not many people are adept at thinking at both levels and readily moving from one level to another as the situation demands. Business analysts are particularly good at that.

Selecting the appropriate abstraction level comes into play during requirements elicitation discussions. Stakeholders often dive into high-resolution details from the beginning. However, the facilitator usually finds it more efficient to begin with broad strokes and defer the details.

That’s one reason why I like the use case approach for elicitation. Use cases typically describe needs at a higher level of abstraction than do user stories or individual functional requirements. Let’s get the big picture first and acquire the specifics when we need them.

A facilitator needs to detect when a group is going down into a rabbit hole, distracted prematurely by details and making little progress. Then they can bring the discussion back to focus on the right level for that day’s goals. Are we identifying use cases today or fleshing out the detailed behaviors for a single use case? Are we identifying data objects or determining their individual attributes? All of those discussions are important, but at the right time.

Suppose the team churns out many detailed bits of information like, “Oh, by the way, the userid can’t contain any special characters.” Figuring out what to do with those bits is like assembling a thousand-piece jigsaw puzzle by picking up one piece at a time and wondering, “Where should this one go?” That bottom-up approach isn’t very efficient.

A BA can recognize when multiple pieces of information or requirements can be grouped logically. They might collect related user stories into a use case with multiple alternative flows, for example. That ability to slide easily up and down the abstraction scale is yet another way a talented BA contributes to working effectively with people and information.

In addition, a BA must be able to operate across three time contexts concurrently:

- Past ( Why were certain decisions made?)

- Present (What must the team build now?)

- Future (How is the product expected to evolve in the near, mid, and long term?)

With that time awareness, the BA can look over the horizon in both directions to put today’s work in the proper context.

Superpower #4: Representing Knowledge Effectively

I mentally translate the phrase “writing requirements” to “representing requirements knowledge.” A BA selects the most appropriate ways to represent knowledge for a given situation and audience. Managers sometimes want to see a bullet list or a diagram, whereas developers will need more specifics. Any single representation method likely won’t meet every stakeholder’s needs.

I once reviewed a requirements specification for a consulting client’s next product, a complex electronic device with multiple software and hardware components. The specification included a lengthy table that described various states the device could be in and what happens when certain actions are taken in each state. From reading the table, it was difficult to get an overall picture of how the device operated.

I decided to draw a state-transition diagram to show those various device states and the allowed transitions from one state to another. In the process, I discovered two missing requirements and one erroneous requirement in that table. Having a variety of techniques in my tool kit lets me choose the best one to show information for a particular purpose.

A BA can choose how best to record information for future use and communication. Sometimes you need text to provide all the details so developers know what to build, testers know what to verify, and customers know what to expect. Hierarchically structured text and tables are easier to work with than long narrative paragraphs or bullet lists.

In other situations, a diagram can either replace or, more often, complement text. I consider modeling to be an essential business analysis practice. An experienced BA knows when to create a detailed requirements spec, when some user stories written on sticky notes are adequate, and when to draw pictures.

Superpower #5: Facilitating Collaboration

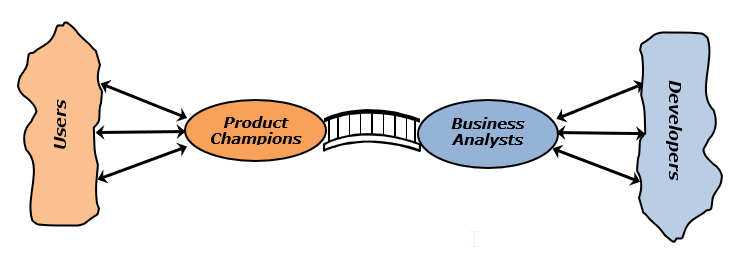

The foundation of effective collaboration is communication. At its core, business analysis is all about communication. The business analyst bridges the gap between a diverse community of users, often represented by product champions, and the development team:

The BA must identify the many stakeholders who have something to say about requirements or are otherwise affected by an initiative. Not all stakeholders carry equal weight, so the BA needs to know which ones have the greatest influence on the many decisions to be made.

Business analysts need to understand each stakeholder community’s goals, concerns, constraints, biases, fears, and pressures. BAs know that the customer is not always right, but the customer always has a point. You must understand and respect the customer’s input. However, you should also point out when a customer is unrealistic or simply wrong. It can be uncomfortable, but this frankness helps the BA guide a team to make good decisions.

I once was the lead BA on a team initiating a project after two previous teams had failed. The primary stakeholder was angry and pressured. “I don’t have time to discuss requirements anymore!” he told me. “Build me a system!” I convinced him that we would apply new techniques (use cases, in particular) and document what we learned. He reluctantly agreed to cooperate. The project was a great success, and the stakeholder was delighted.

We all run what we hear from others through our personal filters. As my colleague Anton expressed it, the BA needs “the ability to listen without bias, premature judgment, or intellectual attachment.” A BA will step out of their own frame of reference to hear the real problems, resist the temptation to impose their own preferences, and guide the participants to define satisfactory solutions.

Stakeholders often present conflicting needs and priorities. If left unresolved, the development team must handle those conflicts. The BA should establish a decision-making process to resolve such conflicts before they impede collaboration. Business analysts can facilitate difficult conversations and negotiations among stakeholders to achieve the optimal outcomes for the business.

In short, the BA’s role includes getting everyone on the same page—and keeping them there.

Are you a Super BA?

If you’re an experienced business analyst, you’ve accumulated a valuable set of knowledge, abilities, and tools. You probably already possess some of these superpowers. Nevertheless, you might have opportunities to beef up your capabilities and become even more effective. Consider performing a skills inventory to see where additional learning and practice could pay off. Then unleash these five powers on your next project to help ensure the organization builds the right solution to solve the real problem for maximum business value.

Author: Karl Wiegers

Karl Wiegers is the Principal Consultant at Process Impact. He’s the author of numerous books, including Software Requirements (with Joy Beatty), Software Requirements Essentials (with Candase Hokanson), Software Development Pearls, The Thoughtless Design of Everyday Things, and Successful Business Analysis Consulting.