Abstract

|

Reading time for this article is less than 10 minutes. It is a revision of my 2014 submission to “Modern Analyst” entitled, Making the Elephant Dance: Strategic Enterprise Analysis. In the past 5 years, things have changed, and I have gained new insight and most important learned new aspects. As a result, this article expands previous material to include: |

- Government agencies, and volunteer services; the term “enterprise” covers these public sector entities as well as private business

- Uses the terms

- “initiative” for a proposed project prior to funding

- "opportunity cost” for forgoing the benefit of the next best alternative due to pursuing another solution

- "disbenefits” for the cost of living (incremental on-going cost) with a solution

- Details the components of a business case including pessimistic, expectations, and optimistic alternatives

- A Summary Table of Economic Indicators with formulas, strengths, weaknesses, and sensitivities

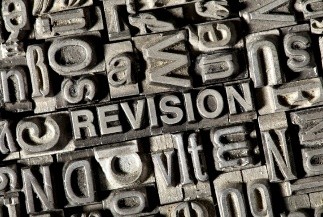

- A Risk Register with risk sources, risk responses, and risk windows

- Clarifies financial analysis level to be an enterprise and/or functional unit effort

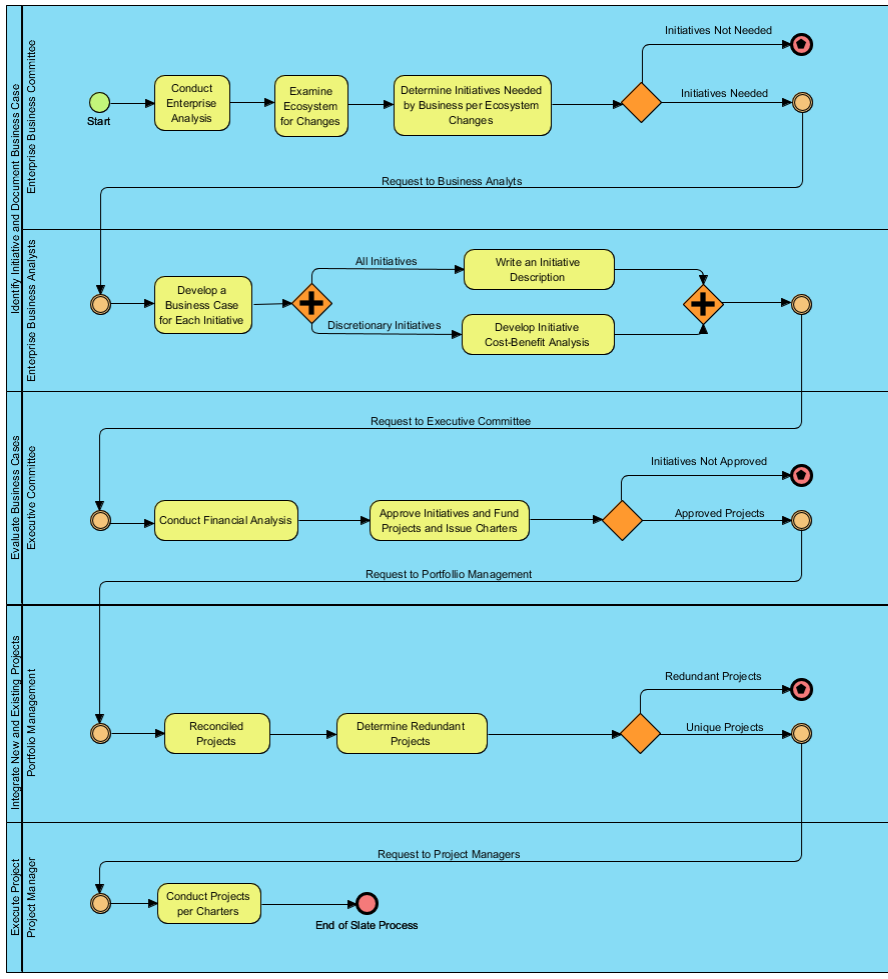

- A Business Process Modeling and Notation (BPMN) diagram on the Strategic Enterprise Analysis process

This revised article provides the background for developing business cases for an enterprise. It starts with analyzing the current enterprise and examines its fit in the ecosystem whether the enterprise be a:

- private business in selling products and services to customers in the private marketplace

- Analysis topics: Do customers still want to purchase the products and services offered by the business? Is the business market share stable or volatile? Has the customer demand changed due to new competition and/or changing needs? Have constraints changed due to new regulations and laws? Has the direction of the business changed due to a new CEO?

- government agency in meeting the needs of its constituents in a regional area (i.e., local, state, national)

- Analysis topics: Are constituents happy with current government products and services? Do constituents need additional product and services due to new regulations and laws (i.e., taxes, job market, housing, crime)? Has the direction of the agency changed due to an election?

- volunteer service in providing services to people in need in the overall public domain

- Analysis examples: Are people still using products and services? Are new product and services needed due to ecosystem events (i.e., social, weather, health, safety, economics)? Has the direction of the service changed due to new leadership?

Note this article uses the traditional term “business case” although the case may be the focus of a government agency or a volunteer service. Many public sector initiatives are now required to justify their needs through a business case. In the public sector, the elected officials or volunteers discuss business cases in terms of both financial and non-financial cost and benefits along with its [1] disbenefits. This allows the agency or service to comprehensively understand the economic impacts.

No matter the enterprise, there is always limited project funding. As a result, a committee of executives needs help in making informed business decisions on what strategic initiatives to fund as projects and in what order. Executives should make these decisions based on facts and financial projections stated in the business case as opposed to just “gut feelings,” hence, the purpose of the business case.

[2]

How are strategic initiatives identified?

|

Every enterprise whether it be a business, agency, or volunteer service has a strategic direction (i.e., mission and vision) based on a previously defined organization structure and how it interacts with the ecosystem (i.e., private marketplace or public domain). However, the enterprise and ecosystem are not stable. They are in constant change: |

- Market Competition

- Product Flexibility

- Risk

- Liability

- Customer / Constituent Demands – causes trends

- Safety Issues

- Government Regulations

- Executive Orders – as a result of organizational personnel changes

- Election Consequences – as a result of elections

Therefore, the strategic direction needs to be validated periodically and changed within the enterprise in order to continue to exist. The executive committee composed of various functional managers (particularly marketing in the private sector), and senior business analysts conduct an enterprise analysis to evaluate the impact change has on the enterprise mission and vision. Based on this analysis, a committee selects strategic initiatives (out of many possibilities) to address needed changes to products, services, processes, skills, or capabilities in order to maintain, advance or set a new strategic direction. The committee’s senior business analysts document these initiatives as business cases for executive consideration.

Note, a business case is not a sales promotion. It focuses on motivation and financials rather than the features of the product or service proposed. The information in a business case may be used in a project charter, but it is not a project charter per se; project charters are follow-on documents that provide project managers with referential authority to execute a project.

What does a business case consist of?

A business case consists of two main components: a description and a cost-benefit analysis of solution alternatives. (1) A description consisting of facts that justify the initiative by utilizing the five W’s of journalism, the four sources of risk, and the business impacts. (2) A cost-benefits analysis that cites the internal economics for each solution alternative. The cost-benefit analysis cites appropriate economic indicators based on stakeholder estimates of benefits in the form of income, savings, and costs to acquire including opportunity cost and cost to maintain (disbenefits) alternative solutions to further justify the initiative. Typically, the business case identifies alternative solutions as pessimistic, expected, and optimistic.

- Description

- Five W’s of Journalism

- Who – organizations involved

- What – product or service proposed

- When – implementation timeframe

- Where – local or global

- Why – alignment to strategic plan, acquisition, mergers, divestitures, changes needed to value propositions, elections (internal/external), part of an existing program, cost reduction, potential revenue gain

- The four sources of risk in developing business cases and projects (see Risk Register)

- Assumptions – conditions to remain true; the primary risk source in the business case; other risk sources may be included, and certainly in projects

- Constraints – limitations in scope, timeframe, business rules, resources, funding

- Dependencies – initiative involved with other existing initiatives or projects

- Resistance – organization and individual barriers to initiative associated change

- Business Impacts

- Value Propositions – product and/or service changes

- Customer – interface changes due to new value propositions

- Employee – new skills needed due to process and/or technology changes

- Process – modifications or redesign of procedures

- Technology – new or unproven

- Facilities – location and/or equipment changes

- Cost-Benefit Analysis - The five economic indicators (see Summary Table for Economic Indicators for strengths, weaknesses, and sensitivities)

- Payback Period

- Return On Investment

- Benefit-Cost Ratio

- Net Present Value

- [3] When using hurdle Rates - Internal Rate of Return (IRR) or Modified Internal Rate of Return (MIRR)

[4] Summary Table for Economic Indicators

Risk Register

Financial Analysis: comparing business cases

Once the enterprise has a complete set of business cases, the enterprise proceeds with comparing the business cases and transforming initiatives to funded projects. Note this activity can be conducted on multiple levels: enterprise and/or functional units.

There are two types of business cases: nondiscretionary and discretionary. Executives evaluate them separately due their nature:

- Nondiscretionary – These business cases are mandatory and are mainly evaluated on their descriptions. Typically, they focus on:

- Law compliance issues, audit decisions or consent decrees

- Industry standards

- Safety concerns

- Executive orders

- Discretionary – These business cases are optional investments and are evaluated on both their description and economics that:Contribute to accomplishing business goals and objectives

- Set a new strategic direction

- Change a value proposition to be in-line to customer demands

- Reduce costs, but maintain quality

- Increase revenue

Steps for Preparing to Conduct a Financial Analysis

- Establish the level ($$$) of project funding for the enterprise and/or functional unit levels.

- Create two separate business case lists: nondiscretionary and discretionary again for the enterprise and/or functional unit levels.

a. For discretionary initiatives: since discretionary initiatives are optional, the executives can use a hurdle rate to pare down the discretionary list.

i. Establish a hurdle rate range. It consists of the current interest rate, plus a minimum rate of return that is acceptable, set by the executives, plus an estimate of the inflation rate over next 5 years. Note that executives may use a range of hurdle rates in order to include low risk initiatives.

ii. Calculate internal rate of return (IRR) [5] or the modified internal rate of return (MIRR) for each initiative; the recommendation is MIRR.

iii. Only initiatives with IRR or MIRR above the hurdle rate are placed on the potential project list.

3. The end result are two lists

a. Nondiscretionary

b. Discretionary - consisting of only initiatives that pass the hurdle rate

Financial Analysis

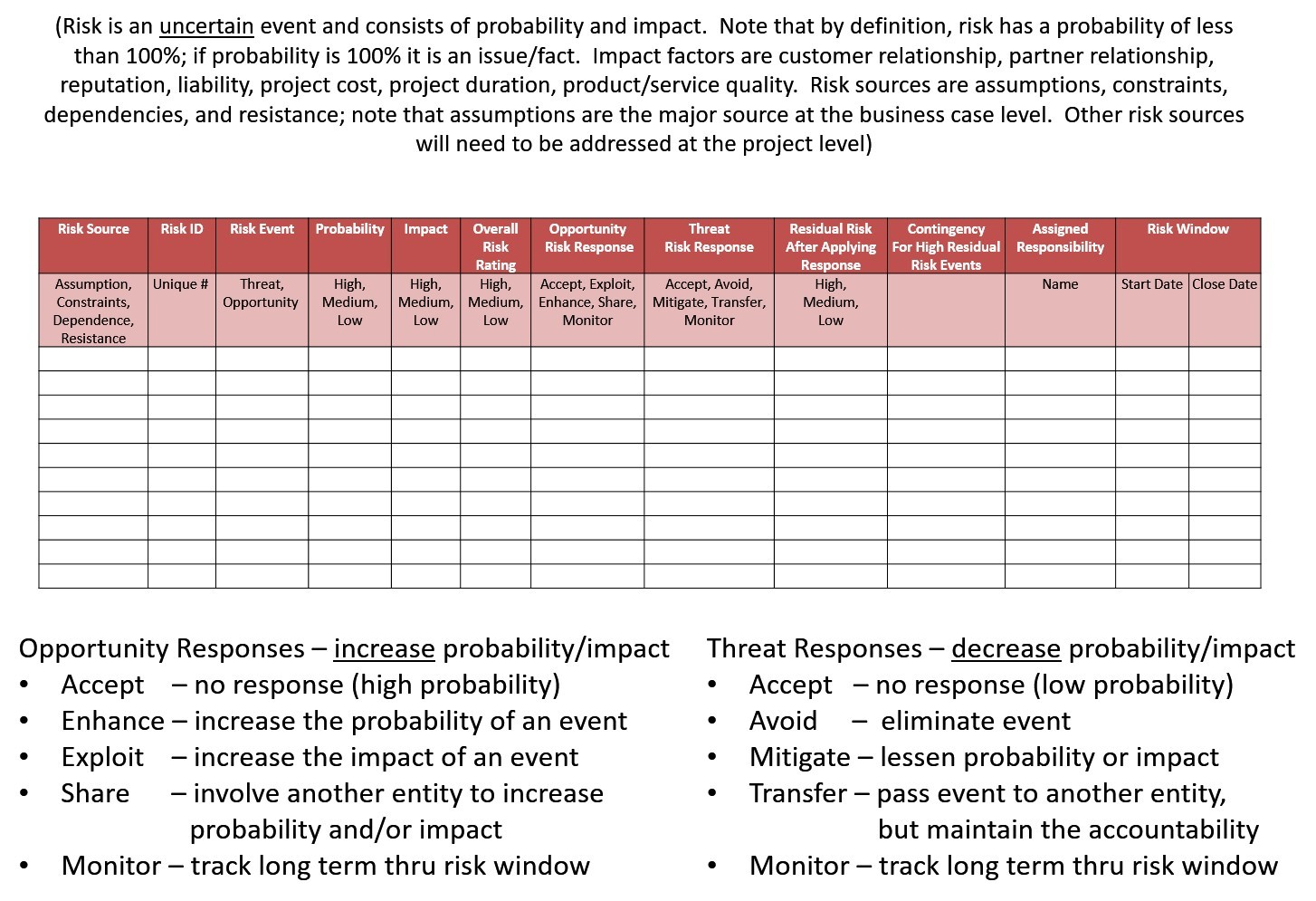

Executives typically use a Comparison Analysis Tool to determine the rank order of nondiscretionary and discretionary initiative lists for funding based on their descriptions and economics. [6] This tool limits the executives to compare only two initiatives at a time and select the preferred initiative. The executives then order the two initiative lists based on the frequency of selection from the highest to the lowest. The end goal is to have two ranked lists with appropriate funding. From these lists, the executives then assign portfolio managers to steward the projects.

Comparison Analysis Tool

Nondiscretionary and Discretionary Initiative Evaluation and Ranking

|

Executives consider the nondiscretionary initiative list first for funding, but this does not mean the executives automatically fund all the initiatives. The executive decision is really when to fund; executives may delay the initiatives depending on |

- how much funding is held in reserve for nondiscretionary initiatives and

- the delay consequences – brand impact, possible fines, incarceration, safety incidents, etc.

Since nondiscretionary initiatives are about motivation rather than cost-benefit, executive focus is on the initiative descriptions in funding decisions rather than the cost-benefit analysis.

After nondiscretionary funding, executives consider the discretionary initiative list. Since discretionary initiatives are about motivation and economics, executive focus is on both initiative descriptions and cost-benefit analysis (see Summary Table of Economic Indicators) in their funding decisions.

Portfolio Management

After the selection of the initiatives (now funded projects), the executives meet with portfolio managers to compare existing projects with the new strategic plan and the list of new projects. The executive board along with the portfolio managers ensures that all projects are

- aligned with the new strategic plan

- unique

If a project is not aligned or redundant, the executive board instructs the appropriate portfolio manager to cancel the project. The executive team approves the proposed projects and assigns each one a sponsor and portfolio manager. In some companies, the executives assign a senior business analyst the responsibility to monitor the realization of the business benefits. Unfortunately, many companies declare victory upon the close of the project rather than monitor the business for the actualization of the project’s business case.

Summary

This article describes the process of the strategic enterprise analysis utilizing text and tables. Below is a Process Chart Management Summary of the strategic enterprise analysis graphically.

Process Chart Management Summary

|

Author: Mr. Monteleone holds a B.S. in physics and an M.S. in computing science from Texas A&M University. He is certified as a Project Management Professional (PMP®) by the Project Management Institute (PMI®), a Certified Business Analysis Professional (CBAP®) by the International Institute of Business Analysis (IIBA®), a Certified ScrumMaster (CSM) and Certified Scrum Product Owner (CSPO) by the Scrum Alliance. He holds an Advanced Master's Certificate in Project Management and a Business Analyst Certification (CBA®) from George Washington University School of Business. Mark is also a member of the Association for the Advancement of Cost Engineering (AACE) and the International Association of Facilitators (IAF). |

Mark is the President of Monteleone Consulting, LLC and author of the book, The 20 Minute Business Analyst: a collection of short articles, humorous stories, and quick reference cards for the busy analyst. He can be contacted via - www.baquickref.com.

References / Footnotes:

1. The cost of living with a solution. See published article in “Modern Analyst” entitled, What are Disbenefits?

2. Other initiatives may also be identified from within the enterprise as continuous improvement, innovations or solutions to internal issues.

3. Note enterprises may use hurdle rates to filter out initiatives that are lower investments. Executive time is precious and hurdles cap the number of initiatives to review. Executives apply hurdles as a range of acceptable returns depending on the initiative risk. The initiative jumps the appropriate hurdle in order to be placed on the review list; see more details “Steps for Preparing to Conduct a Financial Analysis.”

4. Note that the Initial Cost includes any opportunity cost and each year’s Net includes any disbenefits.

5. Note IRR is called internal because the calculation is independent of the external interest rates and any inflation. It is the return on investment that the initiative would break even (i.e., NPV = 0). To be acceptable as a possible project, the IRR should be above the hurdle rate.

However, MIRR is a superior calculation for honing down the project list. Both IRR and MIRR handle reinvestments; however using different interest rates. IRR uses the calculated internal rate of return as the interest rate for reinvestments; this interest rate is often overstated. MIRR uses a separate interest rate for reinvestments.

This difference can be significant.

- For instance, if the hurdle rate is 25% and the IRR is calculated at 50%, the executives would accept the project since the IRR is greater than the hurdle rate not realizing that a 50% reinvestment interest rate was used by the IRR calculation.

- The MIRR in reality may be 20% due to a set interest rate of 5% for reinvestment. The executives should reject the initiative.

6. Note that comparative analysis is competitive. A preferred initiative essentially wins funding from other initiatives. Therefore, if a project does not use all the funding, the funding should be given back for other initiative funding.