JNW, by Howard Podeswa, to be exhibited as part of the group exhibition

The “C” Word, from Feb 8 – Apr 4, 2012. (108x120 inches, oil on canvas)

#3 in the series: “C” is for Class Diagram

This blog continues a series on BA tools, based on my book “The Business Analyst’s Handbook”. In each post, I move through the alphabet, highlighting a BA tool that begins with the letter of the day. Today’s letter is “C” – for Class Diagrams. Business Analysts use Class Diagrams to help them discover ‘structural’ business rules and to document them in a visual form that is readily understood by developers. What is a structural rule? It is any rule that is related to the ‘nouns’ of a business - for example, the rule that only one Salesperson is credited with a Sale (so that sales commissions are never split), or the rule for deriving the amount of the commission for making the Sale. These are considered structural business rules because they are about classes (UML-speak for types) of things within the business – such as SalesPerson or Sale.

Why Class Diagrams Matter to the BA

My company, Noble Inc., is often contracted to help clients set guidelines and good practices for the BAs working in their organizations. Of all the recommendations we make, one that almost invariably meets resistance is for the use of class diagrams (or a similar diagram, the Entity Relationship Diagram [ERD]) as a BA tool. BAs don’t see the point and developers often resent what they see as an intrusion on their turf. In every case, I’ve been able to get developers on-board once they realize that the class diagrams drawn by the BA and those created by the developers represent two very different perspectives: the BA’s model is an abstraction of the real-world business while the developer’s model represents the software solution (specifically, the design model for the software classes and database). Simply put, the BAs aren’t stepping on the developers’ turf because the BA’s class diagrams do not dictate what the solution design will be, they only state the business rules that must be satisfied by the solution – however it is designed. Nevertheless - and BABOK guidelines notwithstanding – my observation is that the practice of drawing class diagrams is not in wide use by BAs. In this blog I’d like to make the argument for why they (or similar diagrams, such as ERDs) are an important BA tool.

Case in Point: The Power of a Simple Sketch

I was speaking with a group of BAs about the requirements for their Human Resources (HR) system. I like to sketch, so as they introduced nouns from the business area, like Employee and Union, I sketched them on a class diagram.

.jpg)

It shows two classes – or categories – of things that are tracked by the business area: Employee and Union.

The sketch was missing a connection between the two, so I asked whether the business needed to know which Employees belonged to which Unions, leading to this version of the diagram.

.jpg)

Now any BA trained in Class Diagrams knows that this diagram is incomplete until numbers are added (two sets for each relationship)– so I asked, “How many Unions may an Employee belong to?” A simple question – and, to be honest, one I already thought I knew the answer to - one Union (per Employee). But the question drew an embarrassed silence. I soon learned that this question – or rather, the failure to ask it - had had costly consequences – namely the decision to purchase an HR system that only supported one Union per Employee. That decision turned out to be a problem because it was possible for an Employee to belong to more than one Union based on his or her collection of responsibilities. That rule is shown below.

.jpg)

(In case you’re wondering how to read the diagram: Read left to right, it states that an Employee belongs to any number of (i.e., zero or more) Unions. Read right to left, it states that a Union has zero or more Employees who belong to it.)

Because nobody thought to ask about this rule, it wasn’t in the requirements documentation, and because it wasn’t there, there was no recourse when the rule was not supported by the software. (In other words, the business had to pay for the fix.)

It’s a small example of the power of a simple sketch.

What we can learn from this example

This little example underscores a few key points about Class Diagrams, and, by extension about structural modeling.

-

Class Diagrams drawn by the BA have everything to do with the business. They are not technical specs.

-

The best time to create class diagrams is during the interview, where they can help reveal missing rules, not later.

-

The model does not have to be formal or complete to be of value. On an agile project, you might only create sketches like the ones above as you facilitate meetings between developers and stakeholders. They still have great value in that context because of the way they help reveal missing business rules.

As always, though, you need to know your audience. You can expect developers to interpret your diagrams exactly as you intended (assuming they are conversant with the UML standard, as many are), but business stakeholders – not so much. Instead, when communicating with them, translate the diagrams back into English.

Business Contexts for the Class Diagram

Like many BA tools, the Class Diagram is an extremely transferrable tool, as you move from business sector to business sector. Some of the contexts in which I’ve used it run the range from the macabre, to the ordinary. These contexts include:

-

Funeral Homes: to capture ways the business needed to store information about deceased individuals, and track their relationships to products (coffins) and grave-site locations.

-

Military: to elicit and document rules regarding military equipment and the maintenance work that relates to it.

-

Travel: to capture rules regarding how travel packages are constructed from Land, Air and Hotel components and how these are billed and ticketed

-

• Manufacturing: to explain to developers how defective components are traced backwards and forwards through the supply chain.

-

Justice systems: To determine how cases are tracked.

-

Customer Relationship Management (CRM): To track how clients are grouped and assigned to agents.

How to read a Class Diagram

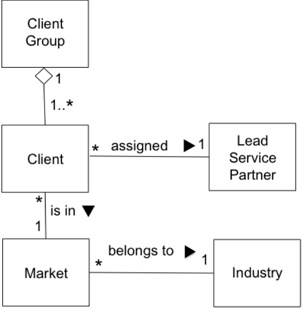

Following is a simplified version of a CRM example. It illustrates most of the Class Diagram features a BA needs to be aware of, except for ‘generalization’. More on that one later:

Let’s start from the top. The boxes, as we’ve seen, are classes – each representing a type of business object (thing) that is tracked by the business. The diamond symbol touching “Client Group” means that Client Group is an “aggregate” - a collection of components. The component part (or parts) is listed on the other end of the relationship; in the example it is “Client”. In other words, a Client Group is made up of Clients. How many? The ‘numbers’ (referred to as multiplicities or cardinalities) are written at either end of each relationship. You can specify:

-

a range: [number]..[number], e.g., 1..5 (meaning 1 through 5)

-

a single number, e.g., 1 (meaning 1 and only 1)

-

a limitless range ending in an asterisk, e.g., 2..* (meaning 2 or more)

-

zero or many: Shown as 0..* or simply, as *

When reading a relationship from one end, you ignore the numeric symbols next to the starting point and use the ones at the far end. In this case, from top to bottom, we read: A Client Group is made up of 1 or more Clients. From bottom to top we read, A Client is a component of one and only one Client Group.

The rest of the diagram can be translated into English as:

-

Each Client is assigned one Lead Service Partner. Each Lead Service Partner is assigned to zero or more Clients.

-

Each Client is in 1 Market. Each Market has zero or more Clients.

-

Each Market belongs to 1 Industry. Each Industry has zero or more Markets.

I think you can see how, strictly from the point of view of understanding the way business terms are used, this is a valuable document. (For example, it explains that an Industry is segmented into Markets, not the other way around.) In addition, it tells the developers about important rules that must be supported by the solution, such as the rule that only one Lead Service Provider is assigned to a Client.

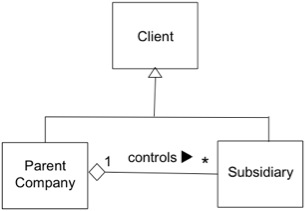

Testing your Class Diagram Prowess

If you think you are ready to tackle a complex model, try this one. It describes the corporate structure of a typical Client. It introduces a new symbol, the arrow (seen below Client), referred to as ‘generalization’. It points to a general type (‘generalized class’) which is broken down into sub-types (‘specialized classes’), indicated at the tail end(s) of the arrow. Here we see that here are two sub-types of Client: A Parent Company and a Subsidiary. Fair enough. But the relationship at the bottom tells us that a Parent Company controls zero or more Subsidiaries and that a Subsidiary is controlled by a single Parent Company. It’s an elegant way to get across the fact that we have two types of Clients and the nature of the relationship between them. In case you’re interested this is an example of a Composite Pattern – and patterns are an advanced topic in Class Diagrams. (So if you understood the diagram, give yourself a pat on the back.)

And – by the way – if you are wondering what the connection is to the painting at the head of this blog, the answer is coincidence (or “synchronicity” – as the Jungians would call it). Just as I am writing this blog on the letter “C”, I am also preparing a painting for shipment to the art exhibit, The “C” Word at the Doris McCarthy Gallery in Toronto. This is that painting. It is a life-size (9 ft x 10 ft) reconstruction of Rembrandt’s The Night Watch, based on measuring high and low points in the original composition.

.jpg) Author: Howard Podeswa is a leader in Business Analysis, having contributed to the formalization of the profession as SME for NITAS, a BA apprenticeship program for CompTIA, as a member of the BABOK review team and as an author. A highly sought-after speaker, he has 30 years experience in many aspects of the I.T. industry, beginning as a developer for Atomic Energy of Canada, Ltd., and continuing as Systems Analyst, Business Analyst, and course designer. He is the author of The Business Analyst’s Handbook and UML for the IT Business Analyst, a practical guide to requirements gathering and documentation for the BA, now in its 2nd edition, published in 3 languages. Through his company, Noble Inc., Howard has provided BA consulting services to a broad range of industry sectors, including health care, defense, energy, government and banking and finance with a diverse client base that includes the Mayo Clinic, Canadian Air Force, the South African Community Peace Program (CPP), Deloitte, the ISO, UST Global (U.S, and India) and BMO/ Harris Bank. In addition, Howard has designed BA training programs for numerous institutions, including CDI (now Global Knowledge), Boston University, Humber College and New Horizons.

Author: Howard Podeswa is a leader in Business Analysis, having contributed to the formalization of the profession as SME for NITAS, a BA apprenticeship program for CompTIA, as a member of the BABOK review team and as an author. A highly sought-after speaker, he has 30 years experience in many aspects of the I.T. industry, beginning as a developer for Atomic Energy of Canada, Ltd., and continuing as Systems Analyst, Business Analyst, and course designer. He is the author of The Business Analyst’s Handbook and UML for the IT Business Analyst, a practical guide to requirements gathering and documentation for the BA, now in its 2nd edition, published in 3 languages. Through his company, Noble Inc., Howard has provided BA consulting services to a broad range of industry sectors, including health care, defense, energy, government and banking and finance with a diverse client base that includes the Mayo Clinic, Canadian Air Force, the South African Community Peace Program (CPP), Deloitte, the ISO, UST Global (U.S, and India) and BMO/ Harris Bank. In addition, Howard has designed BA training programs for numerous institutions, including CDI (now Global Knowledge), Boston University, Humber College and New Horizons.