A business model should include behavioral rules, decision rules, operational business decisions, and operational business events — all as first-class citizens. Understanding their intertwined roles is key to creating top-notch business solutions and business operation systems unmatched in their support for business agility and knowledge retention. This article explains how such true-to-life business models can be created.

| Excerpted with permission from Building Business Solutions: Business Analysis with Business Rules, by Ronald G. Ross with Gladys S.W. Lam, An IIBA® Sponsored Handbook, Business Rule Solutions, LLC, October, 2011, 304 pp, http://www.brsolutions.com/bbs |

Behavioral Rules vs. Decision Rules

Business analysis with business rules focuses on capturing, encoding, and managing a specific kind of knowledge – operational business know-how. (We call it know-how for short.) Know-how is represented in the form of business rules, which in turn are based on a structured business vocabulary.

Decision analysis, a special area of business analysis with business rules, focuses on developing decision rules.[1] Your organization undoubtedly has a great many decision rules, but it also has a great many behavioral rules.

Behavioral rules govern the conduct of on-going business activity by ‘watching’ for violations. Example of a behavioral rule: A student with a failing grade must not be an active member of a sports team.

This business rule is not about selecting the most appropriate sports team for a student, nor does it apply only at a single point of determination (e.g., when a case of a student wanting to join a team comes up). Instead, the business rule is meant to be enforced continuously – for example, if a student who is already active on some sports team should let his or her grades fall. In other words, the business rule is about shaping (governing) the conduct of on-going business activity.

Understanding how behavioral rules work is essential in creating true-to-life business models. Table 1 identifies fundamental differences between behavioral rules and decision rules.

Table 1. Behavioral Rules vs. Decision Rules

| |

Behavioral Rules |

Decision Rules |

| Focus |

Operational business governance |

Operational business decisions |

| Purpose |

Shaping (governing) the conduct of on-going business activity |

Providing answers for repetitive questions arising in day-to-day business activity |

| Featured Kind of Business Rule |

Business rules that can be violated |

Business rules that indicate the correct or best outcome for some case |

| Most Common Original Source |

Interpretation of some law, act, statute, regulation, contract, agreement, business deal, business policy, license, certification, service level agreement, etc. |

Judgments or evaluations made by subject matter experts |

| Special Analysis Techniques |

Pattern Questions [2] |

Q-Charts [3] |

| Role in the Business Model |

Prevent situations (states) the business deems undesirable |

Ensure consistency of operational business decisions |

| Point(s) of Evaluation |

Each operational business event where the business rule could be violated |

The single point of determination in day-to-day business activity at which an operational business decision is made for a case |

| Most Frequent Representation |

Generally fit no pattern, so usually must be expressed as individual statements (e.g., using RuleSpeak[4]) |

Generally fall into patterns, so often can be expressed in decision tables |

| Drill-Down to Additional Business Rules |

Yes, significant drill-down to underlying definitional rules |

Yes, significant drill-down to underlying definitional rules |

| Quantity in a Typical Business Capability |

A great many |

Each decision table has multiple – overall, a great many |

Flash Points

As mentioned above, behavioral rules generally need to be applied at various points in time. What are these points in time? How can you find them? Why are they important for Business Analysts?

Each of the various points in time when a behavioral rule needs to be evaluated represents an operational business event. Such events can arise in either business processes or ad hoc business activity.

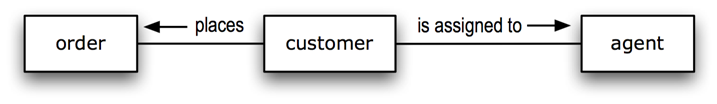

How do you find these operational business events? Consider the behavioral rule: A customer must be assigned to an agent if the customer has placed an order. Figure 1 shows the relevant terms and wordings for this business rule.

Figure 1. Terms and Wordings for the

Agent-Assignment Business Rule

The business rule has been expressed in declarative manner. This means, in part, that it does not indicate any particular process, procedure, or other means to enforce or apply it. It is simply a business rule – nothing more, nothing less.

The business rule makes no reference to any event where it potentially could be violated or needs to be evaluated. The business rule does not say, for example, “When a customer places an order, then ….”

This observation is extremely important for the following reason. “When a customer places an order” is not the only event when the business rule could potentially be violated and therefore needs to be evaluated.

Actually, there is another event when this business rule could be violated: “When an agent leaves our company….” The business rule needs to be evaluated when this event occurs too since the event could pose a violation under the following circumstances: (a) The agent is assigned to a customer, and (b) that customer has placed at least one order.

In other words, the business rule could potentially be violated during two quite distinct kinds of operational business event. The first – “When a customer places an order ...” – is rather obvious. The second – “When an agent leaves our company ...” – might be much less so. Both events are nonetheless important because either could produce a violation of the business rule.

This example is not atypical or unusual in any way. In general, every business rule produces two or more kinds of operational business events where it could potentially be violated or needs to be evaluated. (We mean produces here in the sense of can be analyzed to discover.)

These operational business events are called the business rule’s flash points. Business rules do exist that are specific to an individual event, but they represent a small minority. Two quick notes in passing:

-

Expressing each business rule in declarative form helps ensure none of its flash points is exempted inadvertently.

-

Discovering and analyzing flash points for business rules can also prove useful in validating business rules with business people. Important (and sometimes surprising) business policy questions often crop up.

| |

Your Current Requirements Approach: The Big Question

Each business rule usually produces multiple flash points. Why is this insight so important? The two or more events where any given business rule needs to be evaluated are almost certain to occur within at least two, and possibly many, different processes, procedures, or use cases. Yet for all these different processes, procedures, and use cases there is only a single business rule.

Now ask yourself this: What in your current IT requirements methodology ensures you will get consistent results for each business rule across all these processes, procedures, and use cases?

Unfortunately, the answer today is almost always nothing. In the past, business rules have seldom been treated as a first-class citizen. No wonder legacy systems often act in such unexpected and inconsistent ways(!). Organizations today need business operation systems where business governance, not simply information, is the central concern.

Business rules should be seen as one of the starting points for creating system models – not something designers eventually work down to in use cases. That’s the tail wagging the dog.

By unifying each business rule (single-sourcing), and faithfully supporting all its flash points wherever they occur, Business Analysts can ensure consistent results across all processes, procedures, and use cases. Is there really any other way?!

|

How to Assemble a Know-How Model: Case Study

Let’s walk through a case study to understand how behavioral rules, flash points, and operational business decisions should relate in a business model.

Scenario: A customer places an order.

Flash point: The operational business event “when a customer places an order” is a flash point for some behavioral rule(s).

Behavioral rule: A customer must be assigned to an agent if the customer has placed an order.

Motivation: The business thinking behind the business rule is briefly:

The company’s products are complex, expensive, and available in a large variety of configurations. Customization is often warranted. Assigning an agent helps customers identify the best solution for their particular circumstances. Assisted acquisition also ensures the highest chance of customer success and reduces returns and replacements.

This business thinking is the motivation for the business rule – its pedigree. The motivation should be recorded (as part of rulebook management[5] ) and accessible to everyone properly authorized. Never assume the original motivation for a business rule will be remembered and properly understood by all. Document it!

Violation event: The particular customer placing the order does not have an assigned agent.

Detection of the violation: Some staff person, business rules engine (BRE), or other platform recognizes that an agent needs to be assigned. That staff person, BRE, or other platform did not ‘decide’ the customer needed an agent. No operational business decision or choice among alternatives is needed to recognize the violation. An order being placed by a customer without an agent simply results in a violation of the business rule.

Response to the violation: Something must be done to assign an agent to the customer. When the business rule was created, the company decided the best violation response would be to hand the case over to a line manager and let her handle the situation. Presumably, she’s in the best position to know which agent is optimal to assign to any given customer.

Operational business decision: The need to pick and assign a particular agent from among alternatives for the given customer at the given point in time does represent an operational business decision. The business is trying to answer the question Which is the best agent to assign to a customer? The manager decides and assigns an agent for the given case. Business activity moves on from there.

Potential decision analysis: The operational business decision has been identified and included in a list of possible targets for future decision analysis.

As illustrated by this case study, the dynamics of behavioral rules are fundamentally different from those of decision rules. The differences are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2. Differences in the Dynamics of Behavioral Rules vs. Decision Rules

| |

Behavioral Rules |

Decision Rules |

| Key Concern |

Shaping (governing) on-going business behavior |

What business question is being asked |

| Central Issue for Analysis |

Detection of violations and the appropriate response to such violations |

What is the correct or optimal answer for each case at a given point in time |

| Is Choice Involved? |

A violation of a behavioral rule just happens. No choice is involved in the detection of a violation. |

Choice is center stage. A choice among alternatives (outcomes) is always involved. |

Decision Analysis and Know-How Models

Returning to the agent-assignment rule, let’s say the company recently decided to automate the operational business decision: Which is the best agent to assign to a customer? The Business Analysts will have:

-

Undertaken decision analysis and created a Q-Chart.

-

Developed decision tables, spending time with business leads to get the decision logic right.

Then the decision logic is deployed under a business rule engine (BRE). Now, instead of the line manager performing the decision task ‘manually’ as each case arises, the BRE does it automatically by evaluating the decision tables. No matter, it’s still an operational business decision – a selection or choice among alternatives to be made in real time. Note that the decision logic can be evaluated as a violation response for the original behavioral rule: A customer must be assigned to an agent if the customer has placed an order.

From a business perspective, automation of the operational business decision changed only two things, both for the better:

(1) The line manager has been freed up to do other (perhaps more challenging) work.

(2) Her know-how has been encoded so the company won’t lose it should she leave. Decision logic, like all business rules, is inherently about know-how retention.

When Operational Business Decisions Should Be Made

In the know-how model described above, the decision logic for the operational business decision, Which is the best agent to assign to a customer?, can be invoked as a violation response for the behavioral rule. Do decision rules have flash points too? Yes, but the implicit assumption in decision analysis is that evaluation of decision rules need not be based on their own flash points.

In general, the default point of determination for decision rules is case-based. In other words, an operational business decision is made for a case simply because either the particular case is ready for the decision or the related circumstances demand it.

Example: An order has been filled and packaged and is ready to be shipped to the customer. All behavioral rules have been satisfied. Now the correct or optimal delivery method for shipping the package needs to be selected (an operational business decision). The correct or optimal answer is determined by evaluating the decision rules. Afterwards, things move along as per the business process (e.g., the package is shipped).

Summary

Operational business know-how is complex, involving both behavioral rules and decision rules. Understanding their intertwined roles is key to creating high-quality, true-to-life business models and, from them, effective business operation systems. Treating business rules as a first-class citizen also shifts your focus toward operational business events, especially flash points.

Business Analysts should not work down to business rules in use cases or other system models; business rules should be a primary focus in creating a business model. The resulting true-to-life business model will be unbeatable in its support for business agility and knowledge retention.

About the Authors:

Ronald G. Ross is recognized internationally as the ‘father of business rules.’ He is Co-founder and Principal of Business Rule Solutions, LLC, where he is active in consulting services, publications, the Proteus® methodology, and RuleSpeak®. Mr. Ross serves as Executive Editor of BRCommunity.com and as Chair of the Business Rules Forum Conference. He is the author of nine professional books, including his latest, Building Business Solutions: Business Analysis with Business Rules with Gladys S.W. Lam (2011, http://www.brsolutions.com/bbs), and the authoritative Business Rule Concepts, now in its third edition (2009, http://www.brsolutions.com/b_concepts.php). Mr. Ross speaks and gives popular public seminars across the globe. His blog: http://www.ronross.info/blog/ . Twitter: Ronald_G_Ross

Ronald G. Ross is recognized internationally as the ‘father of business rules.’ He is Co-founder and Principal of Business Rule Solutions, LLC, where he is active in consulting services, publications, the Proteus® methodology, and RuleSpeak®. Mr. Ross serves as Executive Editor of BRCommunity.com and as Chair of the Business Rules Forum Conference. He is the author of nine professional books, including his latest, Building Business Solutions: Business Analysis with Business Rules with Gladys S.W. Lam (2011, http://www.brsolutions.com/bbs), and the authoritative Business Rule Concepts, now in its third edition (2009, http://www.brsolutions.com/b_concepts.php). Mr. Ross speaks and gives popular public seminars across the globe. His blog: http://www.ronross.info/blog/ . Twitter: Ronald_G_Ross

Gladys S.W. Lam is a world-renowned expert on business analysis and applied business rule techniques. She is Co-founder and Principal of Business Rule Solutions, LLC, the most recognized company world-wide for business rule methodology, consulting services, and training. Ms. Lam serves as Publisher of BRCommunity.com and as Executive Director of the Building Business Capabilities (BBC) Conference. She is a recognized authority on project management and is highly active in consulting, mentoring, and training. Ms. Lam co-authored Building Business Solutions: Business Analysis with Business Rules with Ronald G. Ross (2011, http://www.brsolutions.com/bbs). Twitter: GladysLam

Gladys S.W. Lam is a world-renowned expert on business analysis and applied business rule techniques. She is Co-founder and Principal of Business Rule Solutions, LLC, the most recognized company world-wide for business rule methodology, consulting services, and training. Ms. Lam serves as Publisher of BRCommunity.com and as Executive Director of the Building Business Capabilities (BBC) Conference. She is a recognized authority on project management and is highly active in consulting, mentoring, and training. Ms. Lam co-authored Building Business Solutions: Business Analysis with Business Rules with Ronald G. Ross (2011, http://www.brsolutions.com/bbs). Twitter: GladysLam

[1] BRS In-Depth White Paper: Decision Analysis Using Decision Tables and Business Rules. Available free on www.BRSolutions.com.

[2] Refer to Chapters 5, 7, 9, 11, and 15 in Building Business Solutions: Business Analysis with Business Rules, http://www.brsolutions.com/bbs

[3] Ronald G. Ross, "Introducing Question Charts (Q-Charts™) for Analyzing Operational Business Decisions: A New Technique for Getting at Business Rules," Business Rules Journal, Vol. 11, No. 12 (Dec. 2010), URL: http://www.BRCommunity.com/a2010/b567.html

[4] See www.RuleSpeak.com (free)

[5] Refer to Chapter 20 in Building Business Solutions: Business Analysis with Business Rules, http://www.brsolutions.com/bbs