Why Organizations Need Business Analysts

We have always been fascinated by the exceptional business analysts who can create order out of total chaos. The ones who can ask those great questions, who can figure out what’s important and what’s less so, who can synthesize lots of information, put it all into their magic hat and come out with requirements that make sense to all the stakeholders. In other words, the ones with the high tolerance for ambiguity,who know that eventually this mish-mash of requirements, expectations, and semi-articulated wants will come together into a reflection of the real business needs.

We have always been fascinated by the exceptional business analysts who can create order out of total chaos. The ones who can ask those great questions, who can figure out what’s important and what’s less so, who can synthesize lots of information, put it all into their magic hat and come out with requirements that make sense to all the stakeholders. In other words, the ones with the high tolerance for ambiguity,who know that eventually this mish-mash of requirements, expectations, and semi-articulated wants will come together into a reflection of the real business needs.

We are also aware that Project Management requires a different skill set thanBusiness Analysis. It’s not that we can’t wear both hats. It’s just that the hats really are different. And although we both have worn each hat for well over a decade apiece, we both love the ambiguous nature of Business Analysis. As a project manager one of the authors couldn’t leave Business Analysis alone. sheusually attended all the requirements workshops, despite having truly capable business analysts on the project.The excuse she used was that I was nervous about the schedule.Truth be told, it was because requirements activities were the favorite part of her job.Why was it so muchmore interesting to me than project management?

The missing piece fell into place when we attended this year’s PMI North American Global Congress. A session was presented by Michel Thiry, MSc, PMP, whom we have known for several years. His presentation made an interesting distinction between uncertainty and ambiguity. And while he didn’t mention it, he provided a framework which could be applied to Business Analysis.

Uncertainty. As PMs understand, the less we know, the more uncertainty there is, and therefore the greater risk. As we move throughout the project, more becomes known, and what was uncertain is now certain, so the risk decreases. There are many things we can do to reduce uncertainty, such as decompose our projects, deliverables, and tasks, or to manage risks. So even if a project is complicated, it is not necessarily complex or ambiguous.

Ambiguity. Ambiguity differs from uncertainty. While reducing uncertainty is linear, reducing ambiguity happens iteratively. In Business Analysis terms, we ask a question and the answer temporarily reduces ambiguity. However, answering one question leads to more questions. We ask more questions, get more answers, and each answer reduces the ambiguity related only to that specific question. But more questions generally arise. As Thiry points out, in an ambiguous environment, decisions have to be made before the full impacts are known, and much of what we know is learned through retrospection.

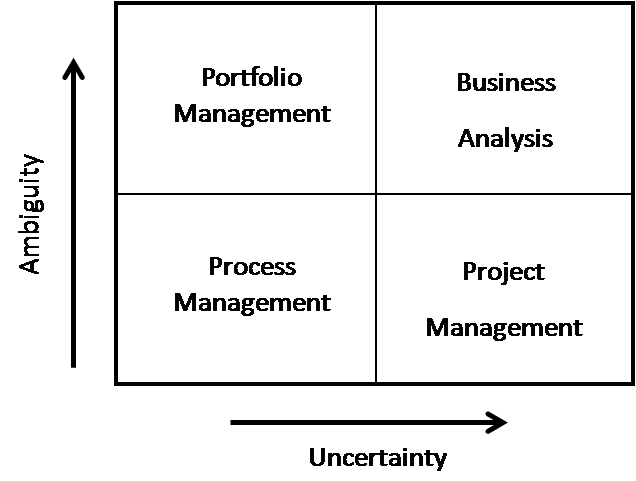

HUHA Matrix. Thiry has developed a simple matrix of uncertainty and ambiguity related to project management. We refined two of the quadrants on the matrix by clarifying the disciplines that define them. See Table 1 below.

On one axis we measure ambiguity going from low to high. On the other we measure uncertainty going from low to high. There are four quadrants. In the lower left quadrant are those activities that are lower in uncertainty and lower in ambiguity (LULA). These are the day-to-day operations where people perform processes, and Business Process Management helps to maximize process assets. Project Management falls in the low ambiguity/high uncertainty quadrant (HULA). Portfolio Management falls into the low uncertainty/high ambiguity quadrant (LUHA).

Sitting through Michel’s presentation, it struck us independently (and immediately) that Business Analysis was the best discipline to address the high ambiguity/high uncertainty (HUHA) situations as shown in Table 1.The best BAs do bring “order out of chaos” and contribute to reduced ambiguity.

An interesting side-note to this framework, it seems to us, is that organizations are most productive when they can reduce ambiguity and uncertainty. This means using Business Analysis, Portfolio Management, and Project Management to solve business problems and seize opportunities, ultimately moving the results towards the LULA quadrant of Process Management. But, that’s a whole other article!

Table 1 – Uncertainty/Ambiguity Matrix, Modified from Michel Thiry’s

Contextualization of the Project Organization [1]

What causes so much ambiguity in requirements? There are many reasons. Business SMEs change their minds. Or they don’t know what they want. Or they know what they want, but they can’t articulate it. Or they think they know what they want, but when we start asking questions, it becomes apparent that they don’t. Or they present a solution without understanding their real business needs. Or they present what they think management wants. The list goes on and on.

As an example, if you build a house, can you imagine not changing your mind as your house is being built and you see the frame added, then the roof, the floors, and the details of the kitchens, bedroom, etc.? What gardener keeps their initial design? They learn that certain plants do better or worse in certain locations. Trees grow and provide more shade. Or they die and shade plants suddenly get exposed to light. Neighbors move in and build walls, or plant their own trees. Things change.

To be sure, there are many requirements analysis techniques that provide a structure to help formulate questions to more quickly reduce ambiguity. Process, data, and use case models help uncover different aspects of requirements. Mock-ups and prototypes provide concrete “pictures” that help the business visualize the end product before time and money are spent developing it.

The iterative nature of Agile methods, such as Scrum, also helps reduce both uncertainty and ambiguity. They help to reduce uncertainty through early delivery, that is, breaking requirements into small features and functions which are delivered iteratively, usually every few weeks. Agile methods help reduce ambiguity by providing a mechanism for responding to change, because we cannot predict the consequences and impacts of decisions made during one iteration on future iterations. An important part of ambiguity, according to Thiry, is learning through retrospection, again, because the future is unpredictable.

But none of these is the silver bullet businesses have been craving since the beginning of time. Business Analysis operates in the realm of both high uncertainty and high ambiguity and the great BAs navigate this terrain expertly. No wonder BAs are so important to project and organizational success!

Authors: Elizabeth Larson and Richard Larson

Authors: Elizabeth Larson and Richard Larson

Elizabeth Larson, CBAP, PMP, CSM and Richard Larson, CBAP, PMP are Co-Principals of Watermark Learning, a globally recognized business analysis and project management training company. With over 30 years of industry experience each, they have used their expertise to help thousands of BA and PM practitioners develop new skills. Their speaking history includes repeat appearances at IIBA and PMI Global Congresses, chapter meetings, and professional development days, as well as BA World conferences.

They have co-written the acclaimed CBAP Certification Study Guide and The Practitioners’ Guide to Requirements Management. They have been quoted in PM Network and CIO magazine. They were lead contributors to the BABOK Guide® Version 2.0, as well as the PMBOK Guide® – Fourth edition.

[1] PMI Global Congress 2011, Ambiguity Management: The New Frontier, by Michel Thiry, MSc, PMP