Summary

The ownership of business processes is often a bone of contention – with various parties feeling that they should be considered the owner of certain processes and not of other processes. Inability to agree on ownership can lead to turf-wars when there are perceived overlaps, as well as impactful inaction when no clear owner has been identified.

This article analyses the source of ownership conflict, and makes suggestions regarding resolutions to the problem. It considers the issue of ownership, as well as the issue of custodianship.

Because of movement of people, skills and responsibilities into an organisation, out of an organisation, and between various work-groups with an organisation, ownership will always be fluid. There will seldom be a static “forever picture”. To facilitate the active management of the identification, and communication of ownership and various custodianship roles, this article also contains a proposal for a business process ownership database.

1. The ownership problem

1.1. Ownership

In general society, even outside of the corporate workplace, ownership is often a problem - a two-way problem. Sometimes multiple parties want exclusive use of an “object” and conflicts arise, whether these are military, ideological, or company-political in nature. At other times nobody wants to acknowledge ownership of an “object”, usually because of onerous responsibilities or social distaste – often resulting in the lack of care of, and subsequent degradation of the non-desired object, leading to a societal loss.

Ownership is an abstract human relational concept. The parties claiming or disclaiming ownership as well as the objects of desire/disgust, do not in themselves alter depending on whether a specific party is or is not recognised as the owner of the object. What alters is the human perception of the rights and obligations that arise between parties because of the abstract status of “ownership”. Ownership can therefore be both a blessing and a curse. Which it is depends on the relative value placed by people on the balance between the social costs and benefits of acknowledging or rejecting ownership.

Ownership is an abstract human relational concept. The parties claiming or disclaiming ownership as well as the objects of desire/disgust, do not in themselves alter depending on whether a specific party is or is not recognised as the owner of the object. What alters is the human perception of the rights and obligations that arise between parties because of the abstract status of “ownership”. Ownership can therefore be both a blessing and a curse. Which it is depends on the relative value placed by people on the balance between the social costs and benefits of acknowledging or rejecting ownership.

Ownership has another element of relativity to it. Various parties have a real interest in a specific object, but for different reasons. Some parties have a critical survival interest in an object, while others may have only a passing interest in the same object. True ownership can be described as having the primary responsibility for the object with all of the rights and obligations that arise from this recognition. Other parties may indeed have secondary responsibility or interests in an object, but the success or failure of the object has a lesser impact on them than on the party with primary responsibility.

1.2. Ownership in the workplace

In the workplace these same social forces come into play. This is especially true in relation to business processes as the “objects” of ownership. Business processes are company social currency. Social standing in the company is based on how many high value business processes are owned. There are desirable business processes to own, and there are also undesirable business processes, which it seems better to disown. Each business process carries a different level of reward or stigma. These rewards often have both monetary and status value attached to them. Consequently the “good” (high reward, low cost) business processes have high ownership value, while the “bad” (high cost, low reward) business processes have low ownership value. The conflict is obvious – more people would like to claim ownership of, or at least a hefty stake in the “good” processes while disowning responsibility for the “bad” processes.

In the corporate world business processes are often traded like real objects among managers to achieve what they believe to be an equitable balance. When this balance shifts and is perceived to be inequitable by one or more parties, office politics arise. Office politics can be seen as the heat generated by friction over business process ownership in the quest to advance corporate social status.

The parties involved in business process ownership disputes are various layers of management. The actual business process performers and lower level business process owners seldom have much of a say in the higher-level ownership of a business process. They are part of the business process and are often traded between higher-level managers along with the business process itself.

1.3. The cost of unclear ownership and other roles

Unclear business process roles carry a high business cost. These costs can be related to business process ownership gaps and overlaps and resultant confusion and conflicts.

Ownership gaps

Some business processes have a number of stakeholders, but no apparent owners. This results in a gap into which many good ideas disappear. Often a lot of budget and effort is spent on developing an idea, but when it comes to implementation nobody wants to take responsibility for giving a final thumbs-up or thumbs-down decision or allocating portions of their budgets to the required change effort. The work gets filed for future reference and is never heard of again.

Ownership gaps result in monetary and opportunity costs. Some compulsory business process changes as the result of e.g. legislative requirements, systems capacity, or company structural changes are not implemented because the business process owner is unaware of the change, or no clear business process owner has been identified. This may lead to legal risks, adverse auditing findings, actual penalties or bad publicity damaging the corporate brand.

To try and cope with such situations business process change requirements are often broadcast by e-mail, via the grapevine or in corporate publications - hoping that through this shotgun approach all interested parties will somehow get to hear of it, understand the relevance and take action. Often one or more of these expected results do not materialise.

If clear ownership is not evident project managers are also forced to hold huge project initiation sessions, absorbing many hours of expensive company resources, in the bid to cover all bases. All of these actions have high actual and opportunity costs associated with them as people wade through hundreds of e-mails a week, in case there are a few that are relevant, or attend unnecessary meetings “just in case”. A more knowledge-driven targeted approach to the real business process owners can save much of this cost.

Ownership overlaps

Some business processes have a number of stakeholders who all think they are the owners of parts of the process or the whole process. When this overlap happens, each supposed owner often identifies his own strategy for the business process and issues his own process change instructions to conform to his understanding of the purpose of the business process. These conflicting instructions lead to frustration by all parties and confusion for other stakeholders and change agents who have to try and implement the varying changes.

In this confusion change agents tasked with implementing change instructions start playing the role of referee and decide which instructions to implement – effectively creating an additional owner of the disputed business process, and further complicating an already complex situation. The IT department is often stuck in the middle as arbitrator – and scapegoat if things go awry.

There is also a cost to ownership overlaps. Some of these costs are inefficient processes, organisational disharmony and wasted energy that could have been better spent on other business process improvements.

1.4. The benefits of clear ownership and other roles

Establishing clear business process roles holds direct and indirect benefits for a company. Clear business process roles allow management to direct scarce corporate resources towards a more clearly defined target knowing that less time, money and effort will be wasted fighting uncertainty and more resources will be used in achieving company objectives.

1.5. The cause of unclear roles

Unclear business roles result from a number of causes. One of these is the housing of multiple specialist skills in the same work-unit or individual. When a skilled business process owner or performer leaves the company, there is often not one single person who can step into the departing person’s shoes fully. This may be because of gradual accretion of business process ownership over years and even decades without these being explicitly defined. Some processes are irregular or operate on a long cycle. As they are not clearly known, they are not passed on to new owners, or are incompletely passed on.

Another cause is the migration of knowledgeable and skilled individuals from one position in the company to another. They often drag a comet-tail of partial responsibilities along behind them, leaving a trail of confusion as to the real ownership of the business processes. Respect for the knowledge, skills or passion of the departed owner, as well as the departing owner’s own sense of responsibility toward the company means that the ownership boundaries quickly become blurred.

The overall problem can therefore be pinned down to incomplete formal identification of business process ownership. This is closely followed by insufficient attention to transition management whenever there is an organisational restructure or whenever there is movement of people into, out of, or within a work unit.

1.6. The resolution to unclear roles

Resolving the confusion around business process roles is advantageous to all organisational units at all levels. To achieve this there are a few steps to resolve and prevent the situation.

Firstly the importance of a clear-cut ownership paradigm has to be understood by the most senior levels of management of the business area wanting to achieve this. It is of little use if all of the departmental managers in a business unit agree on an ownership model if this is not acknowledged and respected by at least the lowest-level common manager above them in the organisational structure. In other words, the most senior direct business process owner in the business area under scrutiny has to be fully involved in the process.

Secondly, the role matrix has to cover all of the significant roles related to every business process. There must be one and only one primary business process owner for every business process. All other roles have to be clearly identified and responsibilities clearly described. The roles need to be described in terms of position rather than individuals, because managers come and go, but business processes are forever. All of the role players must agree to their inclusion in the responsibility matrix and the scope of their involvement in the business process. Ideally there would be a few general relationship roles with clear definitions accepted and understood by all stakeholders.

Thirdly, the role matrix needs to be maintained. This should happen via a clear transition management process that is invariably followed whenever there is a change of person, structure or function.

1.7. The practical implementation of a role matrix

The debate about who the owner of business processes is has been raging for many years. The general consensus now is that “the business” is the owner of business processes. Few people in the various roles that affect business processes will argue against this conceptual statement.

However at an implementation level there are a wide variety of responses that range from lip-service, (i.e. tacit agreement, yet totally unchecked unilateral changes to various elements of processes by non-owners), to a total abdication of all responsibility by the valid owners, to an over-cautious “wait-and-see” response by business process element custodians.

2. Business process “objects”

2.1. What is a business process

Before we can define business process ownership and other roles, we need to have a common understanding of what a business process is. We can use a common definition that:

A business process is a set of coordinated tasks and activities, conducted by both people and equipment that will lead to accomplishing a specific organisational goal.

2.2. The “objects” that need business process ownership clarity.

In the previous section the term “object” was used to denote any thing that needs to have clear ownership role definitions. These objects require clearer identification when it comes down to practical identification and implementation of an ownership model. One of the objects mentioned earlier was a business process. This is also the primary object. However most business processes can be clearly sub-divided into other objects, each of which could have a sub-owner or other major roles identified with it. The objects that readily come to mind are:

3. Business Process Roles

For the various role-players to work together like a Formula 1 pit-crew to keep a business process well-oiled and tuned for peak performance, everybody must clearly know and accept their roles. There will undoubtedly be some stepping on toes in the beginning, but as the team practices more and is reminded of the role responsibilities repeatedly, the team dynamics should become evident. The primary person in the team must be the business process owner to whose benefit it is that roles are clear and that the team works well. This role must not be allowed to be watered down or abdicated.

The primary focus has been on the role of the business process owner. However, this is not the only role that needs to be clarified in relation to business processes. A more complete (though not exhaustive) list of roles follows:

-

Business process owners

-

Business process performers (users)

-

Business process element custodians

-

Upstream business processes owners

-

Downstream business processes owners

-

Consultants

3.1. Business Process Ownership

Business process ownership is the most critical role in this discussion. It is also the role about which there is the most confusion. It is therefore imperative to understand this role clearly before moving on to the other roles. Here are a few references in the literature on the role of the business process owner.

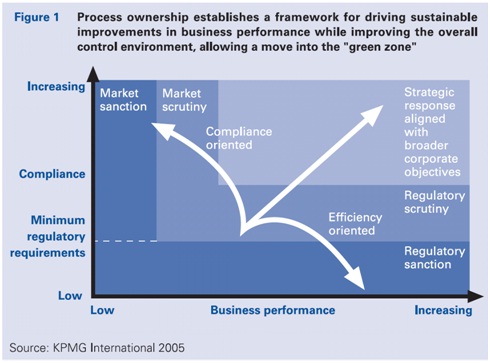

KPMG: “Process owners are appointed with responsibility for the strategic development and health of core business processes. The process owner manages the whole process end-to-end…in order to deliver agreed business results” (Blake: 2005)

Processdriven.org “The process owner is responsible for the process design, not for the performance of the process itself. The process owner is further responsible for the process measurement and feedback systems, the process documentation, and the training of the process performers in its structure and conduct. In essence, the process owner is the person ultimately responsible for improving a process.” (Processdriven.org: 2006)

Booz Allen: Developing effective process owners is never a simple process. It frequently means changing deeply ingrained management perspectives and behaviours. It also means spanning organizational silos and reorienting their management worldview to focus on what links rather than differentiates functions. Companies often complicate this evolution because they fail to adopt incentives to motivate management behaviour in line with the company’s new process orientation. Fundamental decisions about the roles and responsibilities of process owners, and who is best qualified to execute these roles, are paramount to building a strong process-based governance model and to the ultimate success of the entire reengineering initiative. Clear process owner roles offer strong benefits to internal governance. They not only drive how decisions will be made in the future, but also identify and correct potential flaws in the company’s current governance. Exhibit 3 shows a typical job description for a process owner. In many companies, the benefits of introducing these process owner positions include more effective and efficient cross-functional decision-making, fewer cross-functional committees, more single-point ownership, and fewer informal channels to challenge and overturn decisions by escalating decisions to senior executives. What is the background required for successful process owners? Our experience shows that a process owner should:

-

Be an executive or senior manager who possesses organizational clout and can command, not just negotiate

-

Typically be the senior-most manager whose areas of responsibility directly intersect most with the process

-

Have a predisposition to oversee and work with the teams within the core business process and have significant equity across the functions in the business process

-

Possess a broad understanding of the activities and challenges across the business process, with knowledge of upstream and downstream activities (e.g., suppliers and customers)

-

Have the ability to do what is best for the overall performance of the process and its customers, rather than for just the functions or operations falling within the process.

In short, a process owner is not necessarily a subject matter or technical expert, a functional specialist, or an IT-focused process specialist. (Booz Allen: 2003)

Summary

Taking the best out of all these descriptions we can state that process owners are accountable for ensuring that their business processes are as efficient as possible given the available resources (e.g. money, people, time, technology…). The process owner will be measured and then rewarded or sanctioned on the success levels of the processes that they own. There can be no finger pointing. The process buck stops there. Process ownership is an ongoing attitude of personal responsibility, accountability, and constant improvement. A good process owner will make the business process work optimally without excuses, fear, partiality or personal agendas.

3.1.1. So what does a business process owner do?

This is a valid question. It is easier to describe what should be done than to describe how it should be done. Here are some practical suggestions:

-

A business process owner fully understands the responsibilities of the ownership role.

-

A business process owner fully understands the process/function of which s/he is the owner. This means:

-

Understanding the business rationale of the business process, not just what it does. What business purpose does it fulfil?

-

Understand the business rules governing the function and why they exist.

-

Understanding the legal context that governs the business process, if any.

-

Understanding the data elements that are critical to the function, who owns them, where they reside, who creates them, and who else uses them.

-

Understanding which supporting systems there are, what they do (in functional terms), and who the technical custodians are.

-

Understanding the inputs to the business process.

-

Understanding the outputs of the business process.

-

Understanding the transformations that happen in the business process.

-

A business process owner must understand the upstream business processes that create critical data or work for the owned business process.

-

A business process owner must understand the downstream business processes for which the owned business process creates critical data or work.

-

A business process owner must understand all of the other role-player’s responsibility and work at eliminating gaps and overlaps so that the owned process can function optimally.

-

A business process owner must ensure that his/her business process changes as business requirements, legal frameworks, technology, upstream processes and downstream processes change, or as weaknesses, opportunities or threats are identified.

-

As the process owner has to be answerable at the end of the day, no changes to their processes may be done without their explicit consent. This means business rules, forms, manual processes, systems processes, supporting systems and supporting data, whether these elements are shared with other process owners or not.

-

A business process owner can delegate aspects of the business process role to lower-level business process owners or to custodians.

-

A lower-level business process owner inherits decisions re custodianship from a higher-level business process owner.

How is business process ownership established?

There are two typical ways of acquiring business process ownership. The more structured way is that it devolves from a higher-level owner down organisational management lines. The more unstructured, but common way is that a business process is deliberately or by default shunted off to a willing person because there is no identified owner, or it is lumped together with a group of vaguely similar processes, or the designated owner is not managing it properly and responsibility is subtly shifted to a new owner.

How are structured business process ownership responsibilities determined?

-

A higher-level owner must identify a lower-level owner.

-

The lower-level owner must fully understand the ownership role.

-

Exactly which processes and functions are included and excluded

-

The scope of and limitations to responsibilities.

-

Escalation paths

-

The roles of all other players, especially higher-level custodianship delegations

-

The lower-level owner must accept the ownership role.

-

The responsibilities must be published and agreed by all role-players in that function/process

-

The business process performer is not usually the business process owner – in other words the lowest level that business process ownership can be devolved to is departmental manager or in exceptional cases possibly team leader (supervisor) level.

3.2. Business Process Performers

The business process performers are the people who actually execute the business rules in relation to a specific task. They accept the input, process the transaction and ensure that the output is correct. They also ensure that other actions have been identified and passed on to the appropriate individuals.

Even though the business process performers are usually the most knowledgeable in regard to the operational complexities of the business process they are not usually the business process owners.

3.3. Custodianship

A custodian takes care of a resource that is owned by somebody else. So, for example, one can talk of a school principle being the custodian of the pupils at the school during school hours.

There may be different levels of custodianship, as agreed with the owner. So, for example, a trustee may be empowered to deal freely with the assets in a trust fund set up by a deceased parent, while a friend going on a long trip may entrust you to drive and maintain his car, but not authorise you to sell it.

Business process element custodianship commonly therefore has one or more of the following elements: Limited to specific process elements (e.g. a specific set of IT programs, a specific database); May have a time limit (e.g. a project manager may have temporary custody of a process being changed); Scope restrictions (e.g. budgets, timing); Other requirements (e.g. problem escalation boundaries)

The general responsibilities of the various process element custodians are similar, namely: Creating new process elements on request of the business process owner, maintaining a process element according to set standards, and within set parameters, keeping the business process owner informed of environmental factors that may have an impact on the business process, and never changing a process element without the business process owner’s explicit approval.

3.3.1. The data custodian

A data custodian will ensure that the business process owner’s data is reliable (the latest data), safe (access is controlled), and available (regular backup and recovery procedures are in place)

3.3.2. The technology custodian

A technology custodian will ensure that supporting technology performs according to specification, is robust (i.e. available when needed), keeps abreast of technology trends, and is appropriate for the business need

3.3.3. The project custodian

A project custodian will ensure that the project alters the business processes as agreed and is limited to the business processes as agreed in the scoping exercise.

3.3.4. The business rule custodian

A business rule custodian is usually an expert in some or other specialist area, such as product design, legislative interpretation, or financial accounting. They may even have external fiduciary responsibilities such as those of a legislatively prescribed trustee or public officer. They will usually determine some or all of the business rules when a new product or process is created, and then hand these over to the operational business process owner to implement and maintain. Any proposed changes to these specialist business rules have to be referred back to the originating role for agreement as changing these may have serious consequences such as changing the profitability of a product, impacting compliance or reflecting incorrect management information. This is almost a case of joint ownership. However as joint ownership would create problems the following is suggested:

A business rule custodian will ensure that a business rule is accurately defined, that errors in business rules are brought to the business process owner’s attention, that changes required to existing business rules are brought to the business process owner’s attention timeously, and that rules are not changed without the business process owner’s full knowledge and assent by working through a 3rd party such as IT.

A business rule custodian may also be expected to play an auditing role to ensure that the rules of which they are custodians are correct and would usually be expected to be involved in testing any changes relevant to their area of expertise.

In relation to a business rule custodian, a good business process owner will ensure that business rules are not changed without the business rule custodian’s approval.

3.3.5. The communication custodian

Communication to the outside world represents the face of the organisation. It is therefore important that letters and other communiqués to all external parties, such as customers, business partners, and legal entities portray the vision and ethos of the company. Different product lines may also have different audiences, necessitating different styles of communication. It is therefore important to recognise the role of a communication custodian for all external written communication. From a business process perspective, this requires recognition by the business process owner of the role of communication custodian.

The communication custodian will ensure that the communication is effective in its purpose and that the communication style is appropriate for the target audience

The business process owner’s will ensure that the business content of the communication is factually correct and complies with all internal and external requirements.

3.3.6. The business process custodian

This form of custodianship may seem strange, as it entails the whole business process itself. However, in many cases business process owners are focused on the efficient execution of the various processes of which they are the owners. Their time is taken up with managing their staff and budgets, measuring the performance of their business processes against set standards, identifying deviations and dealing with them. They have to manage conflicts in their various teams, and ensure good cooperation with upstream and downstream business process owners. They have to ensure that staff are recruited, trained, and managed. They have to create management statistics for their own and more senior management reporting purposes. They also perform numerous other functions in managing their departments and work teams. They seldom have the time or the background and expertise to deal with issues such as legal changes, technological issues, and generic process opportunities that cut across the domains of numerous other business process owners.

In such cases the business process custodian comes into play. Using military parlance, the business process custodian acts as a shield and a spy. In the role of a shield this custodian will try and protect the business processes from unnecessary changes. All incoming changes are investigated, turned away if not relevant, and let through if relevant. In the role of a spy, this custodian will gather intelligence regarding opportunities and threats, sift through these to see which have substance and which are not yet real opportunities or threats, and communicate the results to the business process owner.

The exact content of the role will change from organisation to organisation, but here is a typical description.

The business process custodian will:

Ensure a stable operational environment through thorough impact analysis of potential opportunities and risks. He will try and negate or reduce adverse impacts, fully utilise opportunities and ensure a controlled transition through the use of compliant documentation and sufficient testing.

Ensure correct identification, analysis and escalation of systems problems and change requests. Manage the prioritisation and progress of changes, ensure there is adequate coping while the problem is being addressed, identify all impacts of the problem, ensure that these are all addressed and communicate adequately with the business process owner and other stakeholders.

Ensure business process continuity by specifying requirements for disaster recovery and business continuity planning, as well as ensuring adequate documentation and testing of these plans.

Monitor upstream business processes to ensure that there are no unexpected “surprises” such as new products data, processes, or systems that will have an impact on his custodial domain.

Ensuring that downstream business processes are taken into account when altering business processes of which they are custodians.

Actively analyse existing business processes to look for areas of improvement and help the business process owner create a business case and document business requirements. All change approvals still reside in the domain of the business process owner.

Monitor the business process environment and identify potential opportunities or threats to established business processes. These may be technology changes, legislative changes and changes to the general business environment such as industry and competitor trends.

3.3.7. The consultant custodian

Consultants are often engaged by high-level business process owners to provide an external view of business processes, usually with an eye on improving business processes or restructuring business process ownership.

The role of the consultant will vary according to the mandate given by the relevant executive business process owner. As in other role-relationships there are often conflicts between lower-level business process owners, and custodians with regard to the role of the consultant.

It is recommended that the role of consultants in regard to business processes is clearly established, explicitly noted and transparently communicated to all lower-level business process owners.

Consultants often enter an organisation as investigators/advisors, and then later switch roles to change-managers and implementers. It is recommended that each time that a consultant changes roles that there be a renewed explicit and transparent mandate to avoid confusion

4. Managing overlaps and gaps

To avoid overlaps and gaps I suggest that the following process be followed.

4.1. Inventory business processes

A comprehensive list of all business functions/processes/transactions that are owned by a business process owner should be compiled. This should be done at all levels of the business. This will not be an easy exercise, as it needs to be driven right down to the smallest infrequent and ad-hoc transaction, and not only done from a high-level value-chain perspective.

4.2. Identify and manage overlaps

The number of overlaps will be more than one expects, because of the unwritten assumption by multiple parties that they are the owner of a process, while other parties may see them as custodians, or users of the process.

There will have to be a facilitated process, often with the involvement of common higher-level BPOs to help resolve these overlap issues.

4.3. Identify and manage gaps

One of the main problems will be identifying processes that do not have explicit owners. Strangely enough, I expect there to be quite a number of these – possibly more so than overlaps.

Most of these gaps may emerge when custodianship is brought into the picture, as the custodianship lists will have to be retro-correlated to the ownership lists.

4.4. Catalogue the owners of all business processes

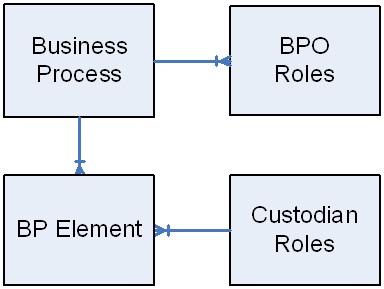

The days of useful paper documents are long gone. I suggest that a company-wide server database be created that holds all of the business process information in the company. This does not need to be a complicated database.

This diagram reads as follows:

-

A company has various business processes that describe its day to day activities.

-

Every business process has multiple levels of owners.

-

Every business process has multiple elements.

-

Every business process element may (or may not) have a custodian (one custodian may be responsible for more than one element).

4.5. Manage the business process owner database

The detailed definition of the database (data normalisation), creating the database on a corporate server, and linking it to the intranet for general availability would be a smallish project.

Populating the known business processes should not take too long per business area.

Establishing the various elements and determining the custodians could be accomplished over time, as this may give rise to considerable discussions and negotiations as roles and responsibilities are clarified.

Updating the database could be a two-stage process. The first stage would be a proposal stage. The second stage would be an acceptance stage. In the proposal stage business functions, their owners, and potential custodians would be entered. The lowest level owner would have to have agreement from one level up regarding ownership. Each of the custodians would have to accept the proposed responsibility.

5. Proposal

I propose that:

-

Every organisation considers establishing a corporate Business Process Ownership database, as broadly defined above.

-

Each business unit identifies a custodian for their processes who would be responsible for ensuring that all business processes are captured, the elements analysed and custodianship agreed to.

-

This database be made available over the intranet for fast identification of the owner of any process in the organisation.

6. List of Sources

This document started off as a much more academic exercise. However time constraints determined a less rigorous approach to finding literature backing for every thought. I may develop this more formally in the future, but here are the references I did use.

Blake, M: 2005 Process Ownership: considerations for successful implementation. KPMG FrontiersInFinance November 2005, issue 44.

Booz Allen: 2003. Process Ownership: The Overlooked Driver of Sustained BPR Success. [Online] Available at http://www.booz.com/media/file/138265.pdf Accessed 3 September 2008.

Processdriven.org: 2006. [Online] Available http://www.processdriven.org. Accessed 3 September 2008.

Author: Robert D’Alton has been involved in business processes for 25 years. 10 of those years have been in various IT roles such as application development, systems analysis, data warehousing, database administration, and IT management. The last 15 years have been spent in various business analysis, and business process management roles at several major South African life insurance companies. He holds a Batchelor of Commerce honours degree in Information Systems management and a Master of Philosophy degree in Futures Studies. He currently heads up a team of 7 and is responsible for business process management functions.

Author: Robert D’Alton has been involved in business processes for 25 years. 10 of those years have been in various IT roles such as application development, systems analysis, data warehousing, database administration, and IT management. The last 15 years have been spent in various business analysis, and business process management roles at several major South African life insurance companies. He holds a Batchelor of Commerce honours degree in Information Systems management and a Master of Philosophy degree in Futures Studies. He currently heads up a team of 7 and is responsible for business process management functions.

All rights reserved.

Article Photo © Tombaky - Fotolia.com