The Business Architecture has slowly emerged as a new and creative way to deliver value to enterprises that have undertaken this strategic initiative. Nearly some ten years ago at the beginning of the 21st century, a search of the web yielded practically nothing on the Business Architecture. This is no longer true as a search today yields thousands of pages of web hits. Even with all of this information, many are rightly questioning the necessity of the Business Architecture, while trying to understand its purpose and realize its value. After all, most enterprises do not have a formal Business Architecture and many do not have plans to develop one.

The Business Architecture has slowly emerged as a new and creative way to deliver value to enterprises that have undertaken this strategic initiative. Nearly some ten years ago at the beginning of the 21st century, a search of the web yielded practically nothing on the Business Architecture. This is no longer true as a search today yields thousands of pages of web hits. Even with all of this information, many are rightly questioning the necessity of the Business Architecture, while trying to understand its purpose and realize its value. After all, most enterprises do not have a formal Business Architecture and many do not have plans to develop one.

Perhaps the results of an experiment run by a CEO may explain the Business Architecture’s necessity. In an executive meeting, the newly appointed CEO asks all attendees to come to a meeting in just one hour to present a model or architecture of the enterprise! What might each executive deliver in their presentation? It is a safe bet that the COO, CFO, CIO and other executives will present different views of the enterprise! Most assuredly, each will present accurate information, and compliment each discussion with a rich and descriptive dialogue. However, each will present some different aspect of the enterprise, just as in the delightful children’s story of the “blind men describing the elephant.”

If each executive posts their respective model on the wall, it is doubtful that one model or architecture will illustrate the relationships with the other models. Their verbal descriptions might explain the relationships, but unless someone records their conversation, most is lost after the presentation. The new CEO could never glean an understanding of the enterprise by simply reviewing the models on the wall and not listening to the presentations. The models are probably not consistent and not rich enough in semantics and syntax to precisely understand their meaning [1].

Consider for a moment the format and content of the executives’ presentations and materials. More than likely, beyond the attractive high-level marketing or sales type slides, there is very little useful substance available for research, analysis, and design. Any models, graphical representations or architectures that are presented are probably out of date, poorly integrated, unavailable to the typical business and IT manager, and consequently are seldom used or exploited when undertaking a major new strategic initiative.

Perhaps the leader of a major strategic initiative will consider a similar experiment! Here again, bringing together the various functional organizations participating in the major strategic initiative and asking the functional managers to present a model or architecture of the enterprise! Most likely, the leader will find “more blind men describing another elephant!” If someone does not believe this, then just try one of these experiments for real, and see what happens!

Realizing the results of the experiments mentioned above, maybe one needs to ask a few questions when considering the Business Architecture!

-

Is it necessary for the senior executives and leaders to have a commonly shared model and view of the enterprise when analyzing strategic initiatives and their priorities?

-

What is the cost of not having a commonly shared model and what is the impact on the strategic initiatives’ effectiveness and efficiency?

-

Were any failed strategic initiatives the result of not having a commonly shared model or might their failure been avoided or mitigated with the insight and understanding found using a Business Architecture?

These are neither simple nor easy to answer questions since the enterprise is a complex and complicated entity. One can not accurately represent this intricacy in three or four colorful slides in a “sales type” presentation. It takes an “engineering type” model, defined with rigor and discipline. Furthermore, viewing the enterprise solely in terms of its functions and organizations is too limited and lacks an understanding of causality. Making significant changes in core enterprise processes require analysis of its impact on other processes. Limiting the analysis to just one or two related functions may result in unpredictable consequences in other functional areas or failure to meet enterprise level performance expectations. If functional performance is optimized, most likely, overall enterprise performance is sub optimized.

If the reader accepts the necessity of the Business Architecture for the moment, then what is the Business Architecture and how is it defined? Various organizations and authors have defined the Business Architecture. The better ones inherit and apply the formal definition of architecture referenced by the world leading consensus-based industry standards of IEEE. An IEEE 1471 website [2] under Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ) defines architecture as "The fundamental organization of a system, embodied in its components, their relationships to each other and the environment, and the principles governing its design and evolution." (Just scroll down to the “So, what is an architecture?” question.) As for the definition of Business Architecture, three definitions are provided for consideration, reference and research:

-

The Business Architecture Working Group (BAWG) defines the Business Architecture as a blueprint of the enterprise that provides a common understanding of the organization and is used to align strategic objectives and tactical demands [3].

-

The Open Group Architecture Framework (TOGAF) defines the Business Architecture as the business strategy, governance, organization, and key business processes information, as well as the interaction between these concepts [4]. (Just click on “Definitions” on the left side of the TOGAF web page, and scroll down to the definition for Business Architecture.)

-

The author of this article states the Enterprise Business Architecture defines the enterprise value streams and their relationships to all external entities, other enterprise value streams, and the events that trigger instantiation; it is a definition of what the enterprise must produce to satisfy its customers, compete in a market, deal with its suppliers, sustain operations, and care for its employees [5]. A value stream is an end-to-end collection of activities that creates a result for a “customer,” who may be the ultimate customer or an internal “end user” of the "value stream." The "value stream" has a clear goal: to satisfy or to delight the customer [6] .

These definitions are complemented by three key Business Architecture tenets that have emerged as generally accepted beliefs and principles from a variety of early BA initiatives [7]:

-

The first and most obvious tenet is that the Business Architecture is an “architecture” of enterprise components, not a juxtaposed or classified list of interesting things collected from the enterprise ecosystem. The Business Architecture is a structure or blueprint, not just a concept, idea, discipline or behavior.

-

The second tenet is the implementation and manifestation of the first tenet; architecture. The purposeful integration of cross-functional, end-to-end activities focused on the customer is the first sign of an emerging enterprise structure; an early awareness of the enterprise blueprint. And of course, the focus on a client, consumer, guest, passenger, patron, citizen, end user, stakeholder and other similar terms are just as valid as customer. This greatly expands up from the typical functional view of the enterprise that has dominated corporate behavior for decades.

-

As successful BPM initiatives completed and others followed, some enterprises began to realize relationships between BPM initiatives were also coming into focus. Not only were there performance improvements within the individual BPM initiatives, but linking or integrating one BPM with another, delivered additional results, efficiencies and synergies. This “BPM integration” actually became an early representation of the Business Architecture and the third tenet.

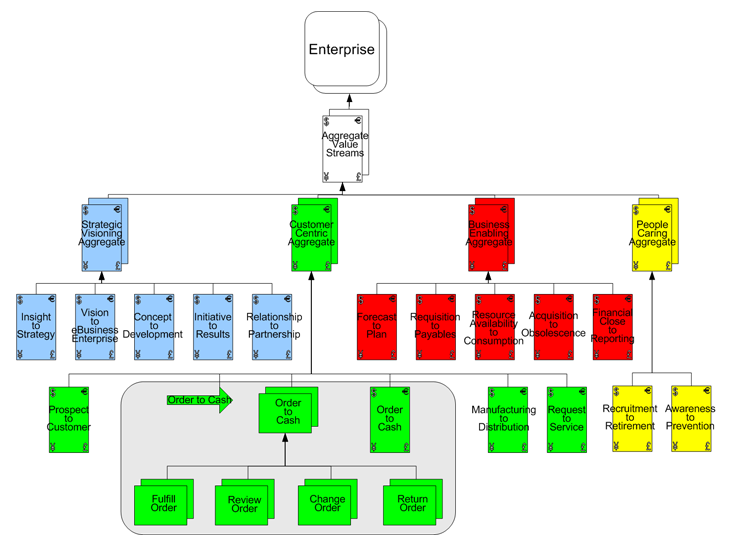

As the reader should realize, the Business Architecture is a formal enterprise structure or blueprint; an “engineering type” model defined with rigor and discipline; not a “sales type” presentation. To see an example of a Business Architecture case study model for a “build to order” manufacturer, one built on the three tenets just discussed, consider Figure 1 following the text of this article. The example presented in Figure 1 is a representative set of value streams as described by James Martin [8], modeled as an Enterprise Business Architecture. The models are best viewed in Internet Explorer 6, 7 or 8 as the hyperlinks are configured for this browser. All models are connected and integrated with one another through their inputs and outputs. All the reader need do is visit the web site and click on the multi-colored rectangles to expose the detail associated with all value streams. Then, once inside a particular model, the reader may again click on the other multi-colored rectangles to understand the integration with other value streams. The Order-to-Cash value stream provides a little more detail for analysis illustrating the focus on the customer. As the reader will observe, the models are connected and integrated with one another in a Business Architecture, designed with a focus on the customer or consumer, representing the integration of all enterprise BPM initiatives; a manifestation of the three tenets.

Experiments, definitions and tenets are interesting, but what about value delivered to the enterprise? Consider this very simple example. The three core cross-functional business processes of Order Fulfillment, Manufacturing/Distribution and Procurement for a “build to order” manufacturer are successfully completed as independent BPM initiatives with excellent results. By integrating these three models in a Business Architecture, one may begin what some call analysis of the enterprise’s value chain [9]. Understanding the relationships between these three core cross-functional business processes from the Business Architecture perspective, additional opportunities for performance improvement will develop. These relationships are the inputs and outputs of the processes. Just consider a few example inputs and outputs. The “sales order” going into Order Fulfillment from the customer represents product demand. The “order release” going into Manufacturing/Distribution from Order Fulfillment represents the go-ahead to build the product. As Manufacturing/Distribution consumes raw materials from inventory, a “purchase order” is created and sent to the appropriate suppliers for replenishment by Procurement. The meticulous management of raw material inventory and the timely replenishment of the “build-to-order” manufacturer’s raw materials are based on actual product demand rather than estimated sales.

Looking at the Business Architecture as an integrated system rather than a collection of isolated processes, a new strategic initiative and opportunity may surface. By working with customers to quickly fulfill “sales orders”, the manufacturer will promptly deliver hot selling items, thereby increasing their customers’ profitability, and increasing their own corporate sales. In a similar manner, working with the suppliers to frequently replenish raw materials used to build those hot selling items; inventories are kept at just-in-time levels, thereby reducing corporate costs. From the value chain perspective, if the “build-to-order” manufacturer can harness the potential of the Business Architecture’s value stream integration in this value chain, then they may achieve a competitive advantage; one of rapidly fulfilling customer orders more quickly than their competitors, supported by raw material inventory managed at just-in-time levels. These kinds of performance improvements are realized by viewing the enterprise as a system enabled by analyzing the Business Architecture.

As one can see, additional opportunities for performance improvements in other core cross-functional processes will develop as additional BPM initiatives complete and get integrated into the Business Architecture. The integrated system of business processes grows and expands as well as the insight to determine new strategic opportunities. Properly developed, managed and leveraged, the Business Architecture complemented with the successful completion of BPM initiatives will deliver the results expected in the strategy. In the above example, improvements such as increasing customer profitability, higher corporate sales and lower corporate costs are achievable and will easily demonstrate the value delivered by the Business Architecture. These are opportunities the enterprise cannot afford to overlook, and perhaps when brought to fruition will lead to a competitive advantage!

Figure 1. Enterprise Hierarchy

References

-

Ralph Whittle and Conrad B. Mryick, Enterprise Business Architecture: The Formal Link between Strategy and Results (CRC Press 2004), page 11.

-

IEEE 1471 website, Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ), http://www.iso-architecture.org/ieee-1471/ieee-1471-faq.html Just scroll down to the question, “So, what is an architecture?

-

Business Architecture Working Group, http://bawg.omg.org/

-

The Open Group Architecture Framework (TOGAF) website, http://www.opengroup.org/architecture/togaf9-doc/arch/ Just click on “Definitions” on the left side of the TOGAF web page, and scroll down to the definition for Business Architecture.

-

Ralph Whittle and Conrad B. Mryick, Enterprise Business Architecture: The Formal Link between Strategy and Results (CRC Press 2004), page 31.

-

James Martin, The Great Transition: Using the Seven Disciplines of Enterprise Engineering to Align People, Technology, and Strategy (American Management Association 1995), page 104.

-

Ralph Whittle, BPMInstitute.org, Articles, “Converging Business Architecture (BA) Approaches,”http://www.bpminstitute.org/articles/article/article/converging-business-architecture-ba-approaches.html.

-

James Martin, The Great Transition: Using the Seven Disciplines of Enterprise Engineering to Align People, Technology, and Strategy (American Management Association 1995), page 104.?

-

Michael E. Porter, Competitive Advantage: Creating and Sustaining Superior Performance (The Free Press 1985), pages 33-34.

Author: Ralph Whittle is co-author of a book titled, Enterprise Business Architecture: The Formal Link between Strategy and Results, CRC Press 2004. He is a Strategic Business/IT Consultant and subject matter expert in Enterprise Business Architecture development and implementation. He is a co-inventor of a patented Strategic Business/IT Planning framework. You can visit his web site at www.enterprisebusinessarchitecture.com or contact him via email at [email protected].

Author: Ralph Whittle is co-author of a book titled, Enterprise Business Architecture: The Formal Link between Strategy and Results, CRC Press 2004. He is a Strategic Business/IT Consultant and subject matter expert in Enterprise Business Architecture development and implementation. He is a co-inventor of a patented Strategic Business/IT Planning framework. You can visit his web site at www.enterprisebusinessarchitecture.com or contact him via email at [email protected].