I am no longer a Webinar virgin. Thanks to the good folks at the IIBA, this week I had my first Webinar experience as an interviewee as part of the IIBA’s ‘ABC’ (Authors, Books and Conversations) series. The host, Julian Sammy, was brilliant in being able to pick out the questions that would be the most difficult for me to answer. (I hear that’s what makes him a great BA, too.) Of course, afterwards, I was regretting not being able to do a ‘do-over’ – until I remembered that I could – sort of – thanks to my MA blog.

Julian’s toughest questions were about the 3-way connection I saw between psychology, business analysis and art; I’ll leave that for later. But there was a BA question that I didn’t have a ready answer for, “What are the most important things you wish you had known when you were starting out as a BA?” Maybe it’s because it’s been so long since I have been in that position. But the memories have begun to come back.

Julian’s toughest questions were about the 3-way connection I saw between psychology, business analysis and art; I’ll leave that for later. But there was a BA question that I didn’t have a ready answer for, “What are the most important things you wish you had known when you were starting out as a BA?” Maybe it’s because it’s been so long since I have been in that position. But the memories have begun to come back.

So, for Julian - and anyone else who might be interested: here, then, after some thought, is what I wished someone had told me when I was starting out:

1. See every BA engagement as an opportunity to learn about other people - and not just to learn about another system: I thought my success or failure as a BA would be all about my analysis skills. I have since found out it hinges more on my ability to connect with people from a wide variety of backgrounds and cultures.

2. Turn off the inner monologue while listening to other people. (See #1 above).

3. Find out, from day 1, who will have ultimate signing authority – then meet that person as soon as possible: I’ve had bad shocks early in my career when I found out that the one person I really needed to convince was the one person I didn’t know about - until it was too late. I now do everything in my power to bring that person into the process ASAP.

4. Don’t go off for too long on your own: In my earlier days, I would do a big round of interviews and then go off for a long period to produce a big ‘tome’ of documentation. I found out soon enough that it’s too much for stakeholders to absorb at once and it’s too easy to propagate mistakes – like too much or the wrong kind of documentation. Now I provide feedback frequently to stakeholders.

5. The only way to get a good user interface is through many iterations of prototyping and user testing – because most people don’t know what they want till they see it. The focus of the BA in this case is to find out what the flow of the interface should be from the user’s perspective (the ‘Basic Flow’ – in use-case parlance), as well as the alternative scenarios that need to be addressed, while the designer works to realize these flows in the prototypes.

6. Test assumptions as early as possible in order to mitigate risk – especially if this is something you (or your organization) is doing for the first time: I’ve personally worked on 2 major projects where untested assumptions about new technology resulted in long delays and lots of rework once they were found to be untrue - and I have direct knowledge of many more projects that have suffered the same fate. By testing assumptions early I am now able to reduce the impact of unexpected problems.

7. Budget your time wisely: In the early days, I blew too much analysis time on small parts of the business area. I am much more careful now in planning and budgeting my time. I’ve learned to work top-down; in the beginning, I concentrate on the big picture and work my down into the weeds as the project progresses.

8. There is almost always a hidden agenda: For any non-trivial project, there is bound to be some aspect of office politics that can make or break the project. In many cases I have ended up being an unwitting pawn in someone else’s power play. In one case, for example, there were warring departments, each of which had already made up its mind about the preferred solution; the hidden agenda of the project champion who brought me onboard was to get an ‘unbiased expert’ to recommend his preference.

9. Don’t solutionize the requirements: The requirements as written, should make sense regardless of the technology solution. Otherwise, they will not be reusable should the preferred solution change – leading to lost time and effort.

10. The clients already know the answer: This is the secret lesson of consulting that I learned at the hands of a colleague (Brian Lyons) – and I’ve found it to be true more often than not. In many cases (such as process improvement projects), the clients know what’s wrong and what they need to do about it - and are really looking to the BA to confirm what they already know, or to help them formulate their thoughts. Yet another reason why it’s more important to listen than to talk.

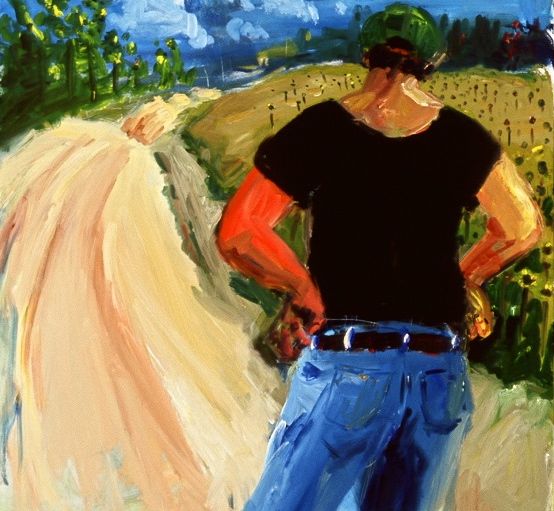

And what about that question about psychology, business analysis and art (all of which are interests of mine)? The flippant answer is to say that these interests co-exist but they don’t necessarily connect. By maybe they do. I have an endless curiosity about people and how they live their lives – and it is a curiosity that the BA profession has helped me satisfy. As well, I have always been interested in the structure of thought – a theme that underlies both cognitive psychology as well as structural analysis. My art similarly has two recurring themes - often concerned either with the psychology of an interaction (see this series based on my experiences in South Africa) or with the way the mind organizes information (see this link for work based on organizing visual bytes of information).

So maybe there is some connecting thread to it after all.

- Howard Podeswa